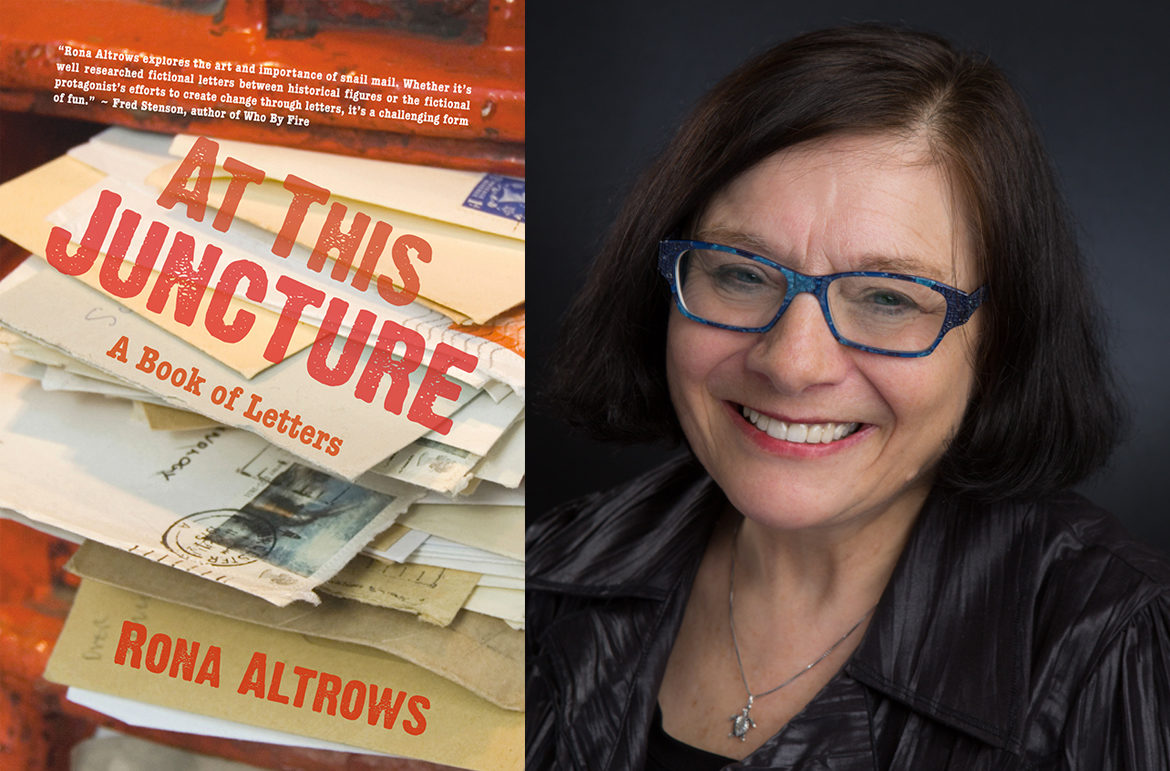

At This Juncture: A Book of Letters by Rona Altrows (Now Or Never Publishing) combines the epistolary format with a charming and humorous narrator—Ariadne Jensen.

Alarmed that Canada Post keeps losing money, Ariadne pitches the CEO with a scheme to save the corporation: she will get people to start writing and mailing letters again. As an inspiration to others, Ariadne writes bundles of letters for all to see. Each letter itself tells a story, while together they form a bigger story—about Ariadne, her determination to set wrongs right, her sly humour, and her loyalty to her best friend.

Rona (and of course Ariadne) graced us with their presence to share their love of snail mail and illuminate a little more about the author and the narrator behind At This Juncture.

How did you get started as a writer, and what genres do you write in?

I’ve been making up stories, songs, poems, since early childhood and have always felt driven to write, but for a long time, I shoved writing into the corners of my life, which was frustrating. Then, in a 1993 TV interview, W.O. Mitchell uttered the words “autobiographical recall” and I felt an instantaneous shift that I can’t explain rationally. Mitchell had, with two words not even directed to me, shown me the way into my own writing life.

The next morning I slammed an open hand on the kitchen table, said “I commit” out loud (although I was alone) and that was it. I went out and bought a bunch of elementary school notebooks and a package of cheap Bic pens, changed jobs, and started to write several hours a day. I wrote uninterrupted autobiographical recall for six months, threw out everything I’d written, then started writing fiction. I’ve been at it ever since. Today I write fiction, essays, plays, hybrids.

What was the impetus for At This Juncture?

My emotional responses to General James Wolfe and Lady Gaga started it and a newspaper article about Canada Post provided the premise.

On a visit to the Canadian Museum of History (then called the Museum of Civilization) I saw a small exhibit about Wolfe, with a write-up that described him as a poetry lover. I got curious about him as a person, read books, found online copies of his real letters. I wondered what was going through his mind the night before the Battle on the Plains of Abraham. If he were to write a letter, knowing he might die the next day, who would he write it to? That’s what led to my imagined letter from Wolfe to his mother. Yet I had a sense that, although I was the one who’d written it, someone else was behind that letter.

At about the same time, I got hit by a phishing attack, with Lady Gaga’s name attached to it, and also one of her fans, a young gay man named Jamey, took his own life because of bullying and left a touching message for her. That’s when the letter to Lady Gaga came. But the style was not what mine would be in a letter. It was much more formal. Then came the signature: Ariadne Jensen. In that letter, I met Ariadne and also learned about her best friend, Leo, a young gay man. And I realized then that it was she who had “written” the Wolfe letter too.

Shortly after that, I learned that Canada Post had once again had a bad year financially. By then Ariadne and I were communicating regularly. I’d say we came up together with her scheme to save Canada Post by getting people to write letters.

The narrator of At This Juncture is Ariadne Jensen and she’s quite the individual! Following along with Ariadne’s personal correspondence, you come to understand her passions, thoughts, and feelings. What kind of research went into Ariadne as a narrator, and is she based on anyone in your life?

I paid attention to her, listened to what she had to say, and tried to do her justice as I acted as her scribe. I didn’t have any model for her in mind. I don’t know of any contemporary woman in her fifties who writes as formally as she does. That’s just her.

If there’s any overlap, it’s with me, as some of her teenage adventures are based on things that happened to me. For example, at fifteen, I told a sailor correspondent a pack of lies about my age and name and everything else, and later ‘fessed up. When I was in university a guy exposed himself to me in two libraries, and the librarians were no help. Both of those experiences come up in letters in At This Juncture.

What got you interested in epistolary novels?

The epistolary form wasn’t a conscious choice by me as the writer Ariadne arose from. I always let the speaker, in this case Ariadne, decide on the form. I do find letters to be a wonderfully flexible form of expression though. And letters were a big part of my early life, so writing them feels natural.

Ariadne’s ersatz historical exchanges are amusing and suck the reader in. Her fictionalized letters between historical and less-than-famous people showed so much heart and yet you can still hear her voice coming through. I nearly forgot they were imagined exchanges with historical figures. What research did you do to write these?

We did the research together, Ariadne and I. When I’m working with a fictional person, and the work is in the first person, I try to do the research as that person. For this book, I read books, watched a movie, used the Internet extensively, read articles. Before long it became evident to me that every letter would take place at a critical or decisive moment in the life or work of the purported writer. But it was what captivated Ariadne’s imagination (as channeled by me, of course) that determined what that moment would be. The title of the book comes from her letter to Prince Charles. ” At this juncture,” that’s pure Ariadne. I would say “at this point” or, more likely, “now.” I think it’s also important to say that I was careful not to alter what we understand of the historical record. What I did was speculate on what people could have said or done, letters they could have written, at certain critical moments, even though they didn’t.

You’ve said you don’t use the word character to describe the people in your books, Why is that, and what does it mean to you?

I do understand that character is an accepted term of art, and I am not outraged or on a campaign to end that. But I wouldn’t call a fictional person a “character”, because the term sounds insulting to me. If I don’t believe in the living reality of my fictional people, who will? Why should Ariadne not be called a person? Is she a lesser being? Yes, fictional people are fictional, but they deserve the same respect as you and me.

What was the hardest letter to write in At This Juncture, and why?

The shortest letter in the book was the hardest to write. It is from Helena Jans to her husband, René Descartes. She’s asking him to come home from an out-of-town meeting with his publisher because their five-year-old has a fever, and she herself is starting to feel sick. It’s so hard to get the words of that letter out. Helena has to convey enough information to her husband to convince him, but not be too wordy, because she needs him to act fast. At the same time, she has to deal with her own feelings and responsibilities. What is worse for a mother than the grave illness of her child? And her having to face that alone. What made it even harder to write that letter was knowing that little Francine died six days later.

You’ve written for both adult and children audiences. What are the key qualities you seek to incorporate in your work?

Honesty, humanity, attention to craft. Let humour bubble up naturally when it wants to, because life is not easy for people of any age, and everyone can use a laugh.

Which book(s) have you reread most in your life?

I keep going back to George Eliot’s work, especially Middlemarch. Such incisive insights into people as individuals, such understanding of social machinations and pressures and the damages wrought by class divisions. Melville is another one I love and return to often, especially the short story “Bartleby the Scrivener,” one of the most moving works of fiction I’ve ever read on mental illness.

Where do you like to take a book and read?

On the couch and in bed. My two favourite spots.

Do you listen to music when you write, and if so, what sort?

Music makes me want to listen to it, not my fictional people, so I don’t use it as a background. But I do like to have real people around, doing their thing as I do mine. Mostly I work at a standing table in a well-lit downtown cafeteria. The other people there tend to be reservoir engineers and entrepreneurs and such, so I don’t get caught up in their conversations, but I stay aware I am not the centre of the world.

What is your favourite food to eat while writing?

While I write, I don’t eat, which is a good thing, because I am eating for a lot of the rest of my waking hours.

What are you reading?

I am reading Cinnamon Gardens by Shyam Selvadurai and loving it.

Recommend a BC book for us.

As far as BC writers go, I admire the writing of Kevin Patterson, especially the novel Consumption. Joy Kogawa‘s Obasan is one of those books that by reading it, you become a better person. And recently I discovered a BC writer named Lynn Easton. In the Malahat Review, I found her personal essay “The Equation,” which is excellent. I’ll be keeping an eye out for more from her.

Rona Altrows is the author of two books of short fiction, a children’s chapbook, and is the co-editor of the anthology Shy with Naomi K. Lewis. Her work has earned several awards, including an IPPY silver medal, the W.O. Mitchell Book Prize, and the 2017 Alberta Literary Award. She lives in Calgary, Alberta.