The following interview is part two of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. It is also part one of our interview with Lorna Crozier. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2020. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Nom de Plume

There’s the sensitive fern, the fragile fern,

the interrupted. There’s willow feather moss,

fire moss, whip broom moss.

There’s poverty oat grass, fox sedge, field

hawkweed, coltsfoot, viper’s bugloss.

And flickering above the seed heads there’s

little sulphur, hoary elfin, northern

cloudywing, splendid palpita snout.

That’s it. My old name’s gone.

I’ll only answer to Splendid Palpita Snout.

Ah, that’s a mouthful! Then let’s try

twelve-spotted skimmer, mudpuppy,

warbling vireo, rose.

Reprinted with permission from The House the Spirit Builds by Lorna Crozier (Douglas & McIntyre, 2019).

Rob Taylor: To start things off, should I refer to you as the “juggernaut of Canadian poetry” (as does the press release for The House the Spirit Builds) or “Splendid Palpita Snout” or just Lorna? I’m open to any of them.

Lorna Crozier: Lorna or Splendid Lorna will do.

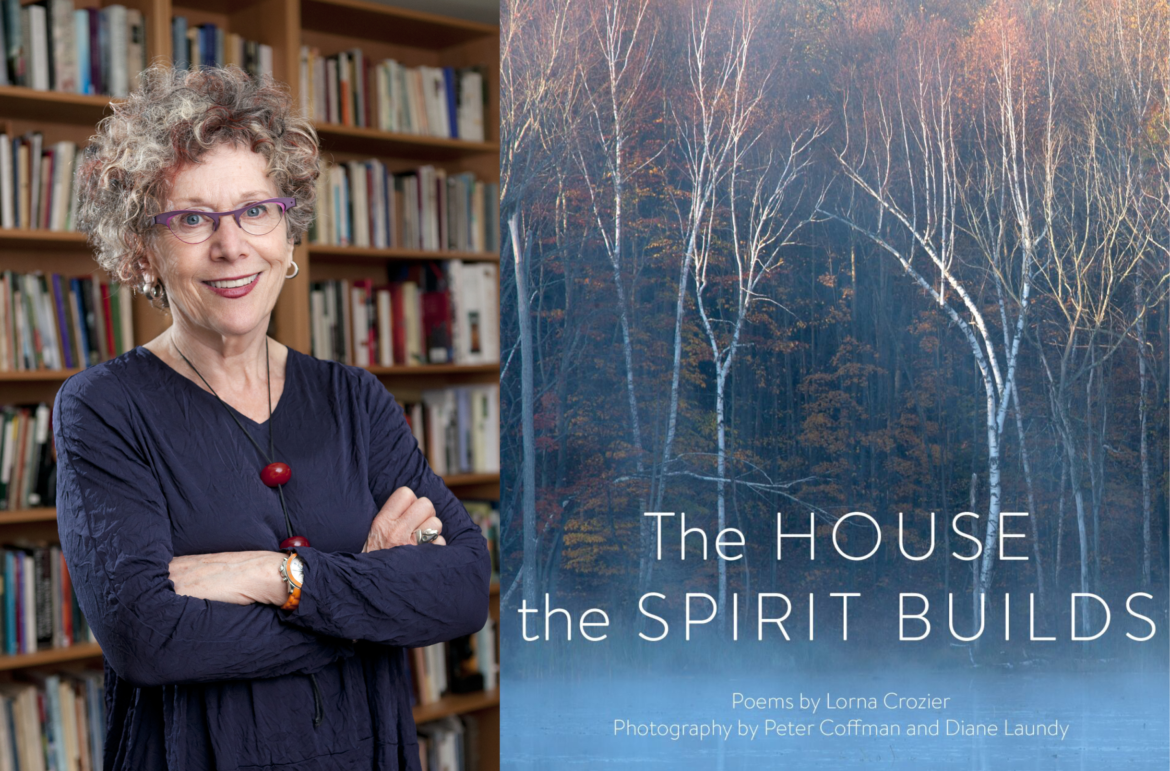

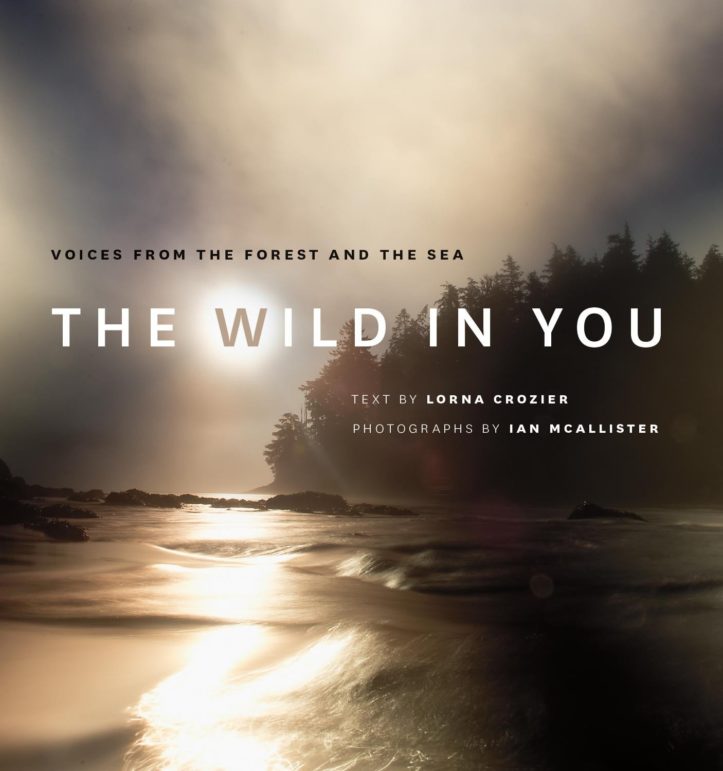

Ok, Splendid Lorna, The House the Spirit Builds will draw obvious comparisons to The Wild in You, your bestselling photos-and-poems “gift book” published by Greystone back in 2015. The location has changed (from BC’s Great Bear Rainforest to Ontario’s Frotenac Arch), as have your collaborators (this time photographers Peter Coffman and Diane Laundy), but in both cases poems alternate with complimentary photographs.

Could you talk a bit about how The Wild in You came together and started you on this multi-book journey of collaborations?

The two projects came about in similar ways. Kim Grey, the editor of Toque and Canoe, commissioned me to write a travel piece about the Great Bear Rainforest and sent me there to do so. She set up a meeting with Ian McAllister and suggested that perhaps he and I could do a book together. Both of us started out with little faith and some suspicion about that ever happening, but we liked each other, we both felt passionate about that particular patch of watery wilderness, and we decided to have a go and see what might occur. Ian sent me photos, and I responded in poems to the ones that sparked my imagination.

I wouldn’t have been up to it had I not focused my attention for so many years on the natural world and had I not been the kind of poet who is influenced by place, the weather and the wind. I’d written a couple of poems inspired by my simply being in the rainforest, not by Ian’s photos. I sent him those and he looked through his archives for what might like to sit beside them. In one case, he had to go out a take a picture of a raven. In all of his years on the coast, he hadn’t photographed a raven. He told me later it was because they hung around his back yard in Bella Bella. It was just too easy for him to find them. His pictures of them were brilliant. I told him if I ever become famous for anything, it will be for forcing Ian McAllister to photograph ravens.

Ha! And a fine legacy it would be. How did The Wild in You lead you into writing The House the Spirit Builds? Though structured the same, the latter feels different – more ekphrastic, for instance, with the poems seeming to be written in direct reply to the photos instead of working more broadly around the same themes or ideas.

“I’d like readers to say, “Ah, that’s the way it is. I’ve never seen that before”

The House the Spirit Builds probably wouldn’t exist were it not for The Wild in You. Rena Upitis, the founder of Wintergreen, where the photos for the second book originated, was smitten by Ian’s and my collaboration and wondered if I’d repeat the process, focusing on the Frontenac Biosphere instead of The Great Bear Rainforest. Once a year for over a decade, I’ve facilitated a poetry workshop at Wintergreen Studio, and it’s become one of my places of regeneration and reconnection with the land. Rena did some artistic matchmaking and set me up with Peter Coffman and Diane Laundy, photographers who’d gone to the studio for private retreats and produced photos that catch not only the beauty of its ecosystem but also the warmth of the objects that define the place and that are smoothed and worn by human hands. The images of objects — a skeleton key, a broken salt shaker, tea cups on a windowsill — pleased me immensely, perhaps because I spent an apprenticeship trying to understand the significance of things when I wrote Book of Marvels: A Compendium of Everyday Things.

Objects, which often outlast us, shimmer with meaning if we look at them closely; the photographers were able to translate that meaning into colour and light and shadow. My job was to translate it into words. It has more to do with discovery than with invention—with seeing what is there rather than imposing from the outside. I’d like readers to say, “Ah, that’s the way it is. I’ve never seen that before,” whether they’re referring to the photo or the poem. This is all to say that the book didn’t try to work around concerns or themes common to the three of us. Instead, we worked around what scenes or images wanted to find the camera’s eye and then rouse the writer into another kind of seeing on the page.

Did knowing that the photos would appear next to the poems change how you “translated” them, some of the pressure of ekphrastic writing having been lifted? Or do you think you would have written them the same way regardless?

I see the poems and photographs as companion pieces, both brushing up against each other and taking on the other’s sheen. The poems aren’t explanations of the visual images or captions—they don’t need any—but both, I hope, offer unexpected responses to what the eye and mind ponder in the world. All of the photos could exist without the poems, and some of the poems could strike off on their own, but I’d be sad if they abandoned one another. Each is stronger because of the other’s presence. At least that was my intent in responding to the photographs, in writing the poems.

You’ve mentioned how attention to the natural world is central to much of your writing and life. In The House the Spirit Builds this is doubly so – both poems and photos about subjects that otherwise might be overlooked, from a toad to a key to a shovel handle to an entire vibrant biosphere you race past on the 401 on your way to Toronto.

As such, it feels so appropriate to have the words of a haiku master, Kobayashi Issa, present in the book (closing the poem about the aforementioned toad). Bashō, Buson and Issa are all mentioned, in one way or another, in your books. Could you speak about the role of these poets and their poems in helping you pay deeper attention to the natural world? Have other poets or artists played a similar role?

I have the deepest of respect for the haiku poets and if I could accomplish what they do in three lines, I’d stick to that limitation. Every good haiku — by such masters as Buson, Bashō, Issa — raises the hair on my arms. There’s a clarity that seems oracular to me. They drop small perfectly formed grenades that explode bees or bells or horse’s farts into your cool contemplations of the natural world and change everything. The leaps they take between the first two lines and the last are rarely found in the poetry we write today. I also love the silence they create around them. These few, bare syllables appear delicately out of a great hush so much vaster than a page. The words pull that hush with them and remind us they are but small whispers in the darkness of not speaking. The silence that is part of the haiku I adore also comes from the smallness of what they describe and the lack of any forceful conclusion. Perhaps because the last two lines of the form they came from, the tanka, have been lopped off, the concluding couplet is always the emptiness of the page, the place where utterance can’t go. Like Bashō’s frog, the three lines in that stillness create ripples that circle out and touch the margins. It’s an active quietness.

Some contemporary poets that take me to similar places and that inspire or help shape my poetic response to the natural world include Charles Wright, Peter Everwine, Patrick Lane (in Winter), Douglas Lougheed (in High Marsh Road), Don McKay, Susan Musgrave (in The Sangan River Meditations), Jane Hirshfield, Robert By (in Silence in the Snowy Fields); more recently, Clea Roberts, Kevin Paul, Randy Lundy, Lise Gaston, Steve Price, Donna Kane.

The concluding couplet is the emptiness of the page – yes!

You spoke earlier of “translating” the objects from Wintergreen, which reminded me of something you said in the afterword to your Wilfred Laurier Poetry Series selected poems, Before the First Word. You write of the prairie, the landscape of your childhood: “the impossibility of translating the place… seduces you into language.” Elsewhere you note that you wish to draw the prairie’s “unbroken, undulating landscape” into your poems without “caging” them.

Your two photo books have both been set in very un-prairie locations. Is the prairie, which first seduced you into language, present when you write about these other places? Has being in BC for so long altered your frame of vision in some way, or will the prairie always be a “first language” through which, in a sense, all other languages you learn are translated?

My mother tongue is Southwest Saskatchewanese, no matter how many years I’ve lived away from my birthplace and the home of my young adulthood. I do think, to loosely paraphrase Eli Mandel, it is the site of first word, first dream, first sorrow, first wonder.

There’s an accent that comes from there (we really draw out our vowels) and a vocabulary. Words like caragana, slough, coulee. Others might know them but we say them more often. Perhaps more important, there’s a paradoxical feeling of being huge and small at the same time. Often you’re the only upright thing for miles. That’s the bigness, but then look how insignificant you are under the vastness of the sky. I believe my poetry is comfortable with paradox and contradiction and that it likes to hold at least two contradictory things at the same time. Maybe that’s why I love poems in series and parts. Here’s one way of looking at something, and here’s another, and one more yet. There’s a feeling when you grow up in a small prairie town that you should leave, that you can’t wait to get out, but once you’ve gone, it refuses to abandon your dreams, your imagination, your artistry. I also think the prairies trained me to open my eyes and look for beauty. It’s more subtle there, it doesn’t smack you in the head like a mountain or an ocean, or a forest of old-growth trees.

“What has this new landscape done to me, my diction, the rhythm in my lines? I don’t know, but I’m sure the influence lies beyond my learning to spell rhododendron.“

At the same time, I’ve lived on Vancouver Island for almost half my adult life and I’ll probably die here. What has this new landscape done to me, my diction, the rhythm in my lines? I don’t know, but I’m sure the influence lies beyond my learning to spell rhododendron. Before Patrick fell ill, we cleared the forest across the road of ivy. Every tree, and there were about 400 of them in the park that separates our property from the ocean. We touched them and they touched us back. We inhaled their scent and they breathed us in. I’ve never felt closer to a forest and a place. That forest is now what I pray too and some days, what I write poems to. In Swift Current, Saskatchewan, there was only one wild tree. This difference between where I was born and where I live now, where I will die, must have changed my poetry, but I don’t know enough at the moment to say how.

On the technical side, what I’ve explored in form since I moved to Vancouver Island, the prose poem, for instance, or the ghazal, might have more to do with my university teaching and the things I had to become familiar with so that I could be a resource to my students. I had to be well read in the forms and some of them captured my interest and I tried them out.

You mention your love of poems-in-series, and that’s made clear in so many of your “project” books – from Book of Marvels to God of Shadows to Bones in Their Wings to the two recent photo books, it’s obvious you are drawn to larger thematic and/or formal structures. Your rate of publication of these types of books seems to be increasing in recent years compared to your publication of “un-themed” general collections. Is this change more about you and your writing practice or about what the book industry is interested in publishing?

I have no idea what the book industry is interested in publishing, except I’m pretty sure it isn’t poetry. So few have continued with their poetry lists, and those that have deserve much appreciation and praise. I write what I have to write, with no expectations except that I might be lucky enough to figure out what it is I need/want to say. I feel fortunate to have been published but I don’t think of that when I start something new. I just try to keep up a sense of discovery and wonder as I move through one poem after another. I have the most fun when I get an idea that takes me beyond the single solitary poem and into a series of them, perhaps a whole book of them. I think that’s because I love a stone with facets. “See how many ends this stick has,” Montaigne wrote. How many ways are there to look at a blackbird, a vegetable garden, a cockroach, a pond in winter? That’s what fascinates me. Glory be to God for dappled things.

Your afterword to Before the First Word delves into language’s capacity to capture and contain the world. You mention the Chinese saying “poetry is like being alive twice” (which chimes well with the many ends of Montaigne’s stick) and then add,

“What a blessing this is… you get to experience all of that again in the small charged world of the poem. There’s the image and then there’s the image finding its way into words. You get a chance to relive the experience. You go deeper, and if you’re lucky, you capture the ephemeral significance of what would otherwise be lost.”

At the same time, you note the limitations of language, when you describe catching a fox’s attention eye-to-eye: “for once, your human language doesn’t get in the way.”

This tension between language’s capacity to help us better see/know the world, and yet at the same time act as a barrier to full engagement with the world, feels present in much of your writing. What do you think poetry can know about the world? What do you think it cannot get at at all? Are there particular subjects/moments in your life that you don’t bring to the page because you know language would only get in the way?

Sometimes I think poetry can be described as a small machine for creating failure. Can a poet ever get it right? Can any word contain all that we feel and think and imagine? There are poems written by others that, for me, reach perfection but I bet the poet didn’t feel that. Yet nothing pays more attention to language than poetry, nothing dusts words off and lets them gleam more than poetry. I always work with that double knowing: words won’t do it but words are all I have. I’ve been cursed/blessed with going back to them time and time again, for almost fifty years, to figure out who I am in my small life on earth. There’s a weight of exultation and a weight of sorrow that language can’t bear. Yet it must bear it if you are a writer, if you are a reader.

“Sometimes I think poetry can be described as a small machine for creating failure. Can a poet ever get it right?”

One of the reasons I love poetry is that it bows to silence. There are spaces after the end of the line and spaces between stanzas and sometimes spaces before you get to the end of the page. Those spaces pay tribute to what can’t be spoken, to pauses, to hesitations, to gaps in our knowing and speaking. When we chose one word, we are gagging dozens of others. Poems, I believe, honour the impossibility of being able to utter something that matters in order to utter something that matters. Only in that state of doubt and doubtless failure can poetry come into being.

* * *

Click here to continue to part two of this interview.

Lorna Crozier is the author of several books including Small Beneath the Sky (Greystone, 2009), The Book of Marvels (Greystone, 2012), and What the Soul Doesn’t Want (Freehand, 2017), which was nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry. She is a professor emerita at the University of Victoria and an officer of the Order of Canada. She lives in North Saanich, BC.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2019 (Biblioasis, 2019). He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC.

Read more 2020 National Poetry Month features here.