The following interview is part five of an eight-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. The series will run from January until the end of April, National Poetry Month. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018).

Pop Culture 1

Why is it so difficult to see the lesbian?… In part because she has been

“ghosted”—or made to seem invisible by culture itself.

—Terry Castle

In the last century the twentieth the late nineteen-nineties everyone wanted

to be a lesbian this may be exaggeration maybe not everyone maybe not

Pope Saint Paul II or John Ashbery or Sarah Palin but many enough lesbians

then being the media darlings of that period of time TV magazines photomontages

the lesbian at last at long long last becoming visible transmuting the zeitgeist

a time out of time refreshingly free of sham

if you can’t bring back the past

in time you can

bring forth the future.

Reprinted with permission from Time Out of Time (Caitlin Press, 2022).

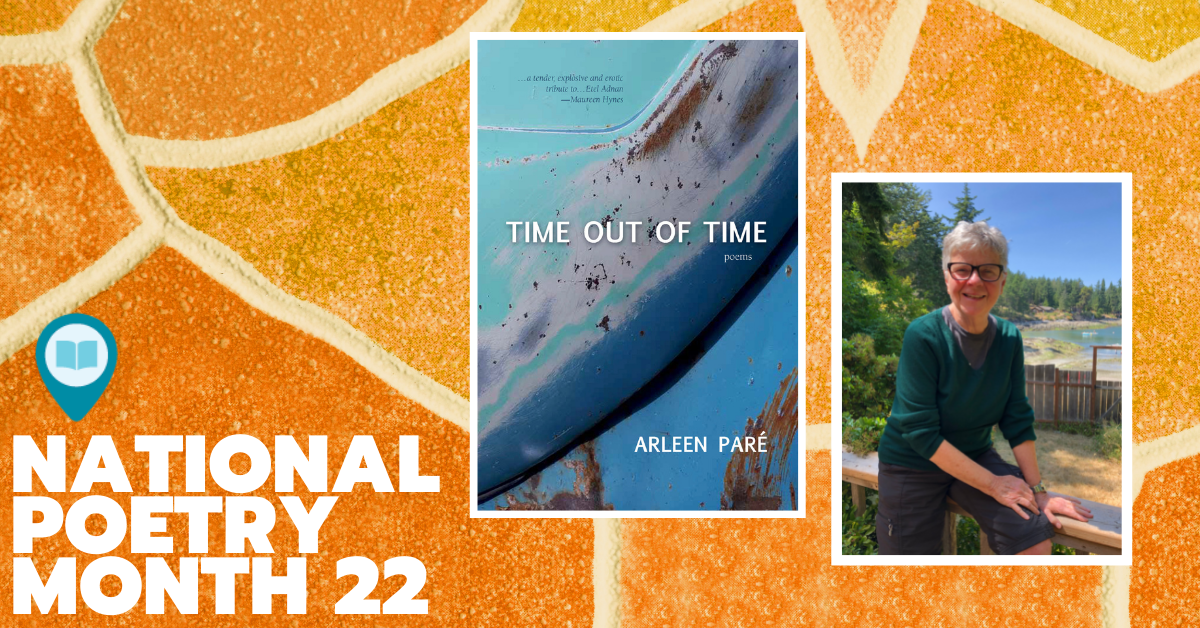

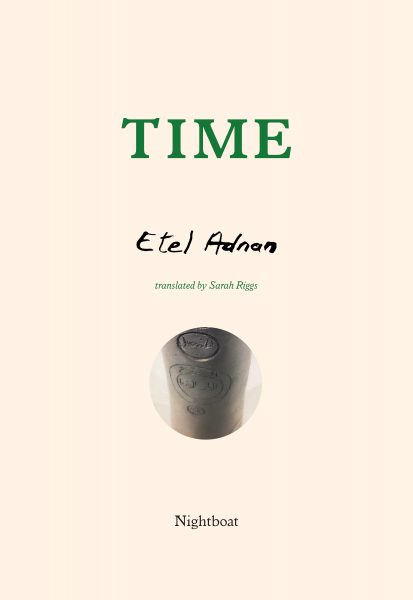

Rob Taylor: Time Out of Time is many things, but perhaps at its heart it’s a love story about reading: how a reader can fall in love with the words of a writer and, in a sense, even with the writer themself. In this case the writer is Lebanese poet Etel Adnan, and the book is her 2020 Griffin Prize winning collection, Time.

“I would follow you anywhere… I don’t even know / what you look like,” you write, and later, “I have fallen in love with an arrant ideal.” Could you tell us more about this one-sided love affair? And would you describe it as “one-sided”?

Arleen Paré: Oh yes, this was a one-sided love affair. Etel Adnan knew me not at all from the vantage point of her very full international life and that was fine with me. People used to ask if I had sent her the manuscript and would I not want her to know that I was writing about her. But no, I was happy that she hadn’t heard of me and my infatuated manuscript. How could she ever have heard a whisper of me? And then she died in November 2021, just as the manuscript was going to print and the possibility was gone. It was a fortuitous crush that enriched my life enormously.

RT: Time Out of Time is a sequence of 49 short, numbered poems, supplemented by a handful of titled poems (including “Pop Culture 1”). This mirrors Adnan’s approach in Time, which contains six numbered sequences. Did you know you were going to mirror Adnan’s style from the beginning, stringing out a book-length project from these smaller responses? Or was the book something you stumbled into, a bit love-drunk?

AP: I knew I wanted to mirror almost everything about Adnan’s poetics in Time; I was entirely smitten with her elegant, spare style. But the project-as-book developed as the month of April 2021, poetry month, the month of writing a poem-a-day, stretched out day by day, poem by poem and suddenly I had over fifteen pages of poetry. By the end of April, I knew I was aiming for a full-length collection. It was an energized period, and I was a little love-drunk. Yes, it was both, stumble and drive. I find I can only really write about someone or something if I begin to fall in love with them.

RT: And you have a lot of love in you! As “Pop Culture 1” demonstrates, Time Out of Time isn’t just a love note to Adnan, but to lesbian writers in general. Your “Notes and Acknowledgments” section in Time Out of Time opens with a list of 138 lesbian and bisexual poets, from Sappho to Adnan to young Canadians, whose poetry “hold[s] you up.” Why was it important to you to expand your praise in this way? Was this always your plan in approaching this project, or did you find your lens widening the more you wrote?

AP: I started by writing with only Etel Adnan in mind, meaning she was the object, but as I added the titled poems, and as the project grew, I knew it was broader, for and about all lesbian poets, in the same way that former women’s and lesbian movements were aimed at and for all women and lesbians. It began to feel more political and yet still very personal. In the way of the old second wave movement saying, “The personal is political.” And how could it be otherwise?

I find I can only really write about someone or something if I begin to fall in love with them.

RT: How has reading lesbian poets shaped your own writing, and your thinking about poetry?

AP: I began to write poetry later in life, as I was approaching (early) retirement. Before that I hadn’t written, or in fact read, poetry, apart from high school English classes. My first poetry teacher, Betsy Warland, is a lesbian, who is political and writes in unconventional ways to emphasize the importance of moving away from the status quo, including as a writer, to expand literary possibilities for those of us who are not entirely a part of the conventional status quo. I was fortunate to have studied with her at the time that I was entering a literary life. She gave me endless permission and a lot of space on the page.

Later I studied more conventional lyric poetry with Lorna Crozier at UVic and with Patrick Lane for decades in poetry retreats. All three teachers are/were incredibly knowledgeable and wise. I feel I have been able to learn from the greats. So while it is supportive to write within a community of lesbians, all of whom have been courageous, and supportive to me in their presence alone, that is not the only support I’ve felt in my rather short-lived writing career.

RT: Speaking of supportive community, while you’ve published a number of books elsewhere, Time Out of Time is your third book with Caitlin Press and first with its relatively new imprint Dagger Editions (“Canada’s Queer Women’s Imprint”). It feels like it must have been important to you to put out this book with this particular press, correct? What does it mean to you to have an imprint dedicated to queer women’s voices in this country?

AP: I am entirely grateful for Vici Johnson’s brave and far-seeing vision for Dagger Editions. I don’t think I could have published this volume with any other press. I thought of them immediately when I thought about publishing Time Out of Time at the end of August last year. It was perfect for Caitlin’s Dagger Editions and Dagger Editions was perfect for me. I think it’s important to have these kinds of outlying presses for those of us who are writing outlying books.

RT: Yes, bless the outlying books! Your vantage point on lesbian love feels a bit different from Adnan’s, who grew up a generation before you in Lebanon, and only came out as a lesbian after having lived for some time in the United States. And at the same time your vantage feels very different from that of a young lesbian writer coming up today. Yet of course there’s a through-line. How do you hope young lesbian readers will come to your own writing on the subject?

AP: Like Etel Adnan, I came out later in life, but during a period of great excitement when the Women’s Movement was at its peak, and so not quite as risky or shameful. I had, perhaps, a more ecstatic entry into the lesbian life, which was quite popular at the time.

As outliers, I think most lesbians are excited to find others, especially in the writing life. It means a lot to find writers with similar concerns. For instance, I recently asked the wonderful young poet and university prof, Annick MacAskill, to host my online launch. She knows my work and we support each other. This was important to me, especially for this book.

RT: In her translator’s note for Time, Adnan’s translator Sarah Riggs writes about translation as a way to “feel the other under your own skin.” Do you think of Time Out of Time as, in its own way, an act of translation? In writing it, were you feeling Adnan under your own skin?

AP: I think Time Out of Time as an act of derivation, not so much as an act of translation. There isn’t anything in Adnan’s (and Sarah Rigg’s translation of) Time that I would want to translate in any direction at all, but I wanted to learn from Adnan’s poetics in Time, and to praise them. My mother used to say that imitation was the sincerest form of flattery. Time Out of Time isn’t, I hope, simple flattery, but true admiration, applause, adoration. On the other hand, I have definitely felt the other under my skin. As writer Charles Bernstein has noted, and [my wife] Chris reminds me, “translation (is) a condition of reading.”

RT: One of the main stylistic elements you draw from Adnan’s poetics in Time Out of Time is brevity. Early in your book, you ask “does brevity not bear / its fair share / of depth”. Was that, in some way, a lesson Adnan was teaching you?

AP: Yes. I was learning brevity from Adnan, receiving permission from her splendid work to attempt brevity, which I admire simply for the fact of brief, but which I have seldom achieved myself. At the same time, I was also recognizing that Sappho’s work is also brief and fragmented in its contemporary iteration and we find it interesting and profound nonetheless.

RT: Another stylistic element present in both books is plain speech. You write, “there were no birds… no roses or grape lilacs… only / words in their best unlilted order // a place for the genuine.” Could you talk more about how “lilted” speech, so often associated with poetry (as are birds and flowers, for that matter!), can get in the way of the genuine?

AP: I often try for ornamentation, which is thrilling in its own right, but Adnan did not strive for ornamentation, almost eschewed it, caring, it seems, only that the poems were true and strong and wise. I wanted to learn from that: add it to my inventory of poetic possibility.

RT: What can unlilted words communicate that lilted words cannot?

AP: Unlilted words convey strength and clarity. These poetics are straightforward, trustworthy, and do not distract the reader in the way that ornamented poetics sometimes can do. At the same time, I admire ornamentation very much. Both lilted and unlilted have their place, I suppose. Time helped me enjoy and admire the unlilted in new ways.

Unlilted words convey strength and clarity. These poetics are straightforward, trustworthy, and do not distract the reader in the way that ornamented poetics sometimes can do.

RT: Writing an entire book around one discrete subject is unusual for many poets, but it kinda seems to be your thing. You’ve written whole books on a lake, a street, a relationship, and a pair of sculptors! Could you talk about this predilection in your writing? Do you really like having a project to write around, or is it more that you get obsessed with something and the project comes later?

AP: Oh yes, I really like to write around a topic or territory, terrain, or heaven forefend, a theme. This allows me to focus all my poetic energies in one gridded direction. I bring out my spotlight and always find places, information, issues, that fit into my current topic. It spurs me to research deeply, and I love to research what I’m trying to poeticize; I learn more carefully and more deeply when I am learning for my poems. I also then get to shape the collection, the narrative. The collection becomes a piece art in itself, a whole. I’m also a very amateur visual artist. I think of a collection visually and in kinetic terms; I find this very satisfying. It adds another ongoing dimension to the project.

RT: Did writing all those themed books better prepare you for writing Time Out of Time?

AP: I think writing all those other themed books did prepare me for writing Time Out of Time. For instance, I began to realize that I was writing a lesbian inflected book, and so when the time came to augment the collection, I knew how I could add those titled lesbian poems and that they would fit right in.

RT: What lessons would you pass on to other poets who were interested in writing a book with a singular focus?

AP: First, find a focus that intrigues you, that you are curious about, that concerns you, that allows you some elbow room. Often it will fall into your lap. It’s waiting for you. Start writing. Research the focus. Keep writing. Maybe even fall in love with the focus. Keep writing. Consider how the focus attracts depth, breadth, tangents. Keep writing. Keep digging. Keep writing.

RT: I think most readers have experienced the thrill of falling in love with a writer, and racing out to a bookstore to find more of their work. Have you had similar surprise “love affairs” previously, with other writers?

AP: Sometimes I fall in love with a poem or a single book, maybe not an author in their totality. My favourite was Don Domanski’s All Our Wonders Unavenged. I love parts of that book. The beginning was a surprise for me — it’s unnerving beauty, wonder and angst.

RT: The love affair isn’t always only with the writer, or the writing, but also sometimes with the physical book itself. In Time Out of Time you write that “the material conditions of this particular bond / is a book / letters and binding and ink,” and elsewhere you write about the journey the physical book took with you through your life (to the bank, into bed, etc.). For you, is the printed book an important element in falling in love with a poet?

AP: I love reading from a hard copy book. I’m a bit of a troglodyte when it comes to books, maybe to everything; I haven’t ever read an ebook. I do listen to audio books but more often when I’m travelling by car.

RT: If books move fully into the digital realm, how do you think reader/writer love affairs might change in the future?

AP: If books shift form clearly into the digital world, my love affairs might end. If I can once again attend in-person readings, though, they may still have a chance; I love listening to a poet read their own words!

RT: We’ve spent all this time talking about your various loves, but we’ve left out, of all people, your wife! Chris Fox, your wife of forty years, is a major recipient of your love in Time Out of Time (“o yes we were forked lightning / and thunder”). At the end of the book, you acknowledge Chris as your “first reader and in-house editor par excellence.” Looking back over Time Out of Time, where do you see Chris’ fingerprints, both as life partner and editor?

AP: Chris is my first editor, first reader and in-house techie, yes, and given how much technological ability is required to move a collection from manuscript to publication and then into marketing and sales, I would not be able to manage this writing business without her. That’s huge. As well, she’s a Canadianist; her doctoral focus was queer Canadian women writers. She also owns an excellent and substantial reference and fiction library, which has been an important contribution to my writing life.

When I thought I wanted to write poetry, later in life, she bought me some of my first poetry collections. We will be celebrating our forty-second anniversary this June.

RT: She must have been patient, watching you fall in love with another woman!

AP: Though she was cognisant of Etel Adnan’s stature and importance in my writing life, she was never jealous of her, a testament to her mostly equanimous, yet romantic, nature. She knows her worth. And I do, too.

Arleen Paré is a Victoria writer with eight collections of poetry, including a recent chapbook. She has been short-listed for the BC Dorothy Livesay BC Award for Poetry and has won the American Golden Crown Award for Poetry, the Victoria Butler Book Prize, a CBC Bookie Award, and a Governor Generals’ Award for Poetry.

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers, was published by Biblioasis in 2021.He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews at: http://roblucastaylor.com/interviews/