The following interview is part one of an eight part series of conversations with BC poets to commemorate National Poetry Month in April. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor.

Mrs. Clean

Yes, he cooks! He cleans!

He writes grocery lists!

But oh, how low

the bar is set.

I should be lucky,

after all most men

aren’t used

to scrubbing a toilet.

My husband’s muscles

bulge against the cotton

of his skin-tight bleached

t-shirt. I’m told he’s ideal

in every way. He won’t touch me

without wearing his yellow rubber

gloves. Yet he plucks hairballs

with bare hands from the neighbour’s

drain. I’ll spike his club soda

with lemon and Clorox. Watch

his bald ass Magic Erase that.

Reprinted with permission from Shapeshifters (Nightwood Editions, 2022)

Rob Taylor: The first third of Shapeshifters is devoted to persona poems, such as “Mrs. Clean.” It’s not until page 32 that we encounter a speaker who resembles some approximation of “Délani Valin.” In your acknowledgments, you thank poet Marilyn Bowering for “suggest[ing], during a time of deep struggle, that I play with different personas as a way to access different experiences.” How did persona poems help you better access the experiences you were struggling with?

Délani Valin: When I came to my writing instructor, Marilyn Bowering, I was in my early twenties and had been writing since I was a child. My problem was that over time, I felt my poetry had become one-dimensional. I was writing the same poem over and over, if I could write at all. In retrospect, I see that I had cornered myself into the narrow identity of Sad Person. I think this was protective: a Sad Person isn’t caught off guard by suffering—she suffers preemptively by numbing out all the time. Yet seeing this numbness reflected back to me again and again in my work didn’t provide me catharsis. I felt alienated from my work and from my body, like I was existing at arm’s length from my own life.

Marilyn assured me that my creativity hadn’t dried up, but that perhaps I needed another point of entry. She suggested writing from different perspectives and personas to avoid the trap of circling around the same poem (and pain) over and over. She gifted me Carol Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife, which was really helpful. Duffy is so witty and I was enamored with the vibrancy in her work.

After trying on a multitude of masks, I was able to glimpse the grounded wearer at the centre of them all.

Why did you choose to focus on corporate mascots?

I grew up with corporate mascots invading everywhere from my school to my pantry and living room. They’re ubiquitous, and many a marketer has hijacked humanity’s gift for stories and fascination with archetypal characters in order to sell yet another variety of cereal. These corporate archetypes are Heroes and Maidens and Mothers. Yet, they’re devoid of agency. My experiment with them was an empathetic effort to imagine their inner lives distinct from the marketers who breathed them into being. But of course, I only substituted my own breath.

Marilyn’s advice about exploring topics through personas brought me closer to myself by opening up a wider breadth of possible expression. After trying on a multitude of masks, I was able to glimpse the grounded wearer at the centre of them all.

In a sense, you pass that journey on to your readers: we access the biographical details of the “grounded wearer at the centre” by traveling first through the persona poems. Was it always important for you to put the persona poems at the beginning? What effect do you hope for that to have on your readers?

This was an area in which Silas White and Emma Skagen at Nightwood Editions were indispensable. When I put together the manuscript, I was unsure about its shape. I thought about putting all of the poems in the exact order I wrote them so that maybe some progression would unfold, but they rattled against each other. I think that it was a case of me being too close to the material to pull back and make sense of it. Once I read it in the order Silas and Emma suggested, it clicked. The shape of the book mirrors the process I had undergone to access my own experiences. It’s like a map.

The poem “Telogen Effluvium” sits, quite literally, at the centre of your book. Named after a hair-loss condition that can sometimes be triggered by psychological or emotional stress, the poem pushes close to discussing a traumatic event, but stops short. On exactly page 48 of a 96 page book, you write, “We just need to know the whole story. Ok, here it is,” but then the next section of the poem is a recipe for a hair mask, and we never fully circle back (though a poem later in the book fills in some details). The result gives a well-like shape to the book: poems stacked carefully around the edges of a dark centre.

I’m always interested in poems where the author is actively wrestling with something on the page (I think of Elizabeth Bishop’s “Write it!” in “One Art“). On the one hand these moments feel emotionally raw and honest, and on the other of course there is always some level of artifice: the poem, even if written in a moment of intensity, was edited and prepared for publication slowly over many months. Could you talk about “Telogen Effluvium,” both how it came to you and how you positioned it within the book?

I wrote “Telogen Effluvium” six months after a traumatic event involving a sexual assault while I was visiting Cotonou, Benin in 2018. What’s interesting is that the other poem that deals more directly with the assault, “Magic Lessons,” was actually written while the event was unfolding and in the immediate aftermath.

They both deal with the circumstances differently. With “Magic Lessons,” my intention had been to write an extended letter to my partner in the form of a travelogue. (As an aside, Benin is an incredible country to visit.) But hell broke loose for me while I was there, and my poem necessarily took a turn.

When I got back from Benin, I was in a bit of a trance and related my story to others many times. I felt this urgency to be seen, to be witnessed. I wanted confirmation that I was still alive and still me. But this also led to me sharing more than was safe for me to do in some cases. Not everyone believed me about what happened, and nor did everyone have the space for my difficult story.

Therefore, when I wrote “Telogen Effluvium,” I was curious about how I could share my story while still protecting myself. I had already absorbed most of the truth of my situation, so I wanted to create a controlled experience where I could anticipate judgement, deflect, and pull back. If I circled around the truth enough, would it come through? Would it be more palatable?

It’s a deeply humbling experience when a reader says they connect with what I’ve written. But if what they’re relating to is a difficult experience or emotion, I want to do my best not to leave us both in that space.

That’s so interesting, that you wrote more directly about the assault initially, but then circled back to a more cautious approach in “Telogen Effluvium.” And then made the choice to present them in the opposite order in the book, like something is being drawn out from you, when really you were reeling it back in. Could you talk a little about the form of “Magic Lessons,” with its six sections, each containing seven tercets, and its many repetitions?

Because I was writing without the benefit of any temporal distance, I knew it was important that I ground the poem in form so that it wouldn’t spiral into a journal entry. The repeating lines served as an anchor, and finding some kind of “lesson” for each section of the poem was actually a helpful tool for meaning-making when the ground beneath me was crumbling at the time of the writing.

It’s fascinating how form can drive meaning-making, pushing you to new and necessary places. “Magic Lessons” isn’t alone in doing this: poems in Shapeshifters are striking in their formal rigour. In addition to more traditional forms, such as glosas, haibun, prose poems, and set stanzaic forms, the book includes forms of your own invention.

One poem, “The Geologist,” is a formal tour de force: it features italicized lines which both can be read as part of the rest of the poem and as its own standalone poem. And if you pluck out the italicized lines, the remaining poem still works! I’ve never read anything quite like it. Could you talk about your interest in form? Does it function for you in some way like the persona poems, a path to access experiences that otherwise prove elusive?

I think that’s right—form serves a similar function to the persona poems, in that forms give me a framework that I can explore and subvert. It also helps the writing stay playful for me. If I’m exploring a difficult personal topic, the form becomes a sort of puzzle. I know I have to hit certain lines or conclude a stanza in a specific way, so in a sense there is a right answer to my “poetry riddle.” It creates a bit of safe distance for me while making sure the writing process is fun.

I also do this in an attempt to care for the reader. It’s a deeply humbling experience when a reader says they connect with what I’ve written. But if what they’re relating to is a difficult experience or emotion, I want to do my best not to leave us both in that space. Pain is inevitable in life, but as someone who has complex trauma or Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD), I feel like it’s my responsibility to be mindful about transferring my particular trauma onto anyone else.

Some of the ways I try to do this are through form, narrative, strategic avoidance, being disciplined about which details I share, and, in some poems, through directly naming this intention. It’s an aspect of my writing that I want to keep developing.

What a generous way to consider your readers, and an interesting way to think about form. One formal element you play with a lot, both in “Magic Lessons” and elsewhere, is long lines—so long they spill over to a second line when squeezed onto the printed page. In this they are reminiscent of poets such as Walt Whitman, Jorie Graham, and C. K. Williams. What inspired you to take on the writing of such long lines? How did long lines affect your sense of what you could say in your poems?

I think the long lines come up for a few reasons. Sometimes it’s to try to capture the way I would tell a story orally—I’m listening for my breaths as I’m writing. Another reason is to give myself space. In conversation with others, it’s often when we stay on one subject just a beat too long that a surprising twist happens. Perhaps we’re discussing something political on a fairly surface level and someone starts to say, “Well, anyway…” but if we stay on the subject just a touch longer, we might discover that they were pivoting because things were actually getting real. It happens to me all the time in conversation, and I try to give a little space for these sorts of insights when I write.

[In] other places, such as “Magic Lessons,” the long lines were an attempt to instill a frantic undercurrent to the poem—though the form is tight, it was a stressful time, so something should reflect that! Beyond that, because the poem deals with magic, the lines are written as a sort of incantation or spell. Ultimately, it’s a spell of self-protection and survival.

Being Métis is an ongoing process: a way of seeing, being, knowing and connecting. Being in relation with other Métis people helped me see this, and made me realize the validity of my own experience.

The closing poem in Shapeshifters is a similar type of spell. In it, you have Cinderella write in her diary, “I killed / my first stepmom but you all // have me clap with songbirds / and cry.” To what extent do you see Shapeshifters as a response to the popular narratives around women’s trauma? In what ways were you trying to tell that story differently here?

The thing about Cinderella is that in some versions of the archetypal story, she does kill her stepmother or even her mother. In others, she flees from advances from her father. Cinderella is afforded more agency in these tales than in most modern retellings.

In the same way that I was sick of my repeating Sad Person poems, I think I was tired of a lifetime of hearing sanitized frail damsel stories. I grew up with Disney and the Bible as a kid, and then I came of age during a time when the damsel was replaced by a stoic “tough chick” trope—a plucky girl who could punch her way through any foe. Essentially, both of these tropes can be summed up as Victims or Survivors. But in either case, these identities comprise ways in which we are totally defined by what happened to us. I don’t think either label suits me. I don’t see myself as a victim or as a survivor. A traumatic event that happened to me is just a thread in a much larger tapestry. I’m not that thread, and nor am I the tapestry. I’m the weaver. I think I wanted to speak to different possibilities.

Beautifully put. Another major part of your “tapestry” is your Métis identity. In “No Buffalos,” you write about your mother, who only at age 40 rediscovered your family’s ancestry (her great-uncle Donald Ross was a member of Louis Riel’s Exovedate and was killed on the final day of fighting at Batoche). You note that despite her lineage and commitment to teaching Métis culture and history, she was still questioned for not having “lived Métis experience.” “Who counts and who decides?” you ask near the end of the poem, “We all have stories, we’re all legitimate.” Can you talk a little about your journey to that last statement?

Being Métis is wonderful. Because of the work my mom does, I’ve been able to embody this truth earlier in life than she had a chance to. She got me involved in jigging when I was a child, and because she became a cultural presenter, I grew up with access to a lot of artifacts and stories.

Still, I have struggled with feelings of displacement. My grandmother was born in Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan, but my mom was born in Hay River, Northwest Territories. My parents met in Edmonton and then moved to my dad’s birthplace, Québec City, which is where I was born. We moved to B.C. when I was nine. There’s been a pervasive feeling of rootlessness threaded through my life, and part of that had contributed to a sense that perhaps I didn’t belong anywhere or to anyone. My family is scattered, and I will always be a guest on Snuneymuxw territory, where I currently reside.

I’ve long had the sense that being Métis isn’t a checkbox we tick off, nor does it end with the knowledge of Métis ancestry. Being Métis is an ongoing process: a way of seeing, being, knowing and connecting. Being in relation with other Métis people helped me see this, and made me realize the validity of my own experience. It echoed the experiences of others, and was in some places distinct.

When I started to live that from my heart, I stopped wondering whether I was Métis “enough.” I work with what I have, I create and maintain relationships wherever I can, and I endeavour to know more, but not because I’m striving to be anyone’s ideal Métis—whatever that is—but because my heart is calling out for it.

A traumatic event that happened to me is just a thread in a much larger tapestry. I’m not that thread, and nor am I the tapestry. I’m the weaver. I think I wanted to speak to different possibilities.

While you were rooting yourself in your family’s Métis heritage, did a similar process play out for you in literature? While reading Shapeshifters, two other Métis poets kept coming to mind: in your mix of formal considerations and Métis history, your poems reminded me of Marilyn Dumont‘s work (especially poems like her sestina “Fiddle Bids Us”), and in your humour and efforts to reconnect to a broken chain of ancestry, they reminded me of Molly Cross-Blanchard‘s poems, such as “First-Time Smudge.”

Those are quite likely just my readerly associations, of course, and you have entirely different ones! “I am also in the broth,” you write in one poem about Métis belonging. Could you talk about the literary broth you see yourself a part of?

Those are great picks. While writing “No Buffalos,” I still mired in self-doubt and was constantly afraid to offend or to get things wrong. I worried that I had no right to speak on any form of Métis experiences, even though I was exploring my own stories. It helped immeasurably to read Indigenous writers like Marilyn Dumont, Louise Bernice Halfe – Skydancer, Daniel David Moses, Gregory Scofield and Lee Maracle for questions of perspective, form, and language.

Writers like Molly Cross-Blanchard, Jónína Kirton, Selina Boan, Jordan Abel and Joshua Whitehead have helped orient me whenever I’ve felt isolated in my explorations. I’m grateful to be able to read so many funny, brilliant, generous, and surprising Indigenous writers. It’s a great time to be reading and writing.

Keeping with Dumont for a minute, like you she had the experience of discovering in her youth that she was related to a prominent Métis leader (in her case, Gabriel Dumont). She waited until her fourth book, The Pemmican Eaters, published twenty years after her debut, to write in detail about that connection. Of this delay, she wrote that her journey to understanding her family’s past “was a lengthy process of historical enquiry and gradual acceptance,” and that perhaps “loyalty to my mother was part of the reason for not writing about Gabriel Dumont before now.” To what extent does Dumont’s slow journey through divided loyalties resonate with your own experience?

I actually see this articulation as a kind of foreshadowing for myself. There are bits and pieces of my personal experience and of my family’s histories (on both sides) that I haven’t explored. I feel the histories still unfolding within me in my day-to-day life, and I’m trusting their timing to float up and be written. I think stories have a say in when they want to be told.

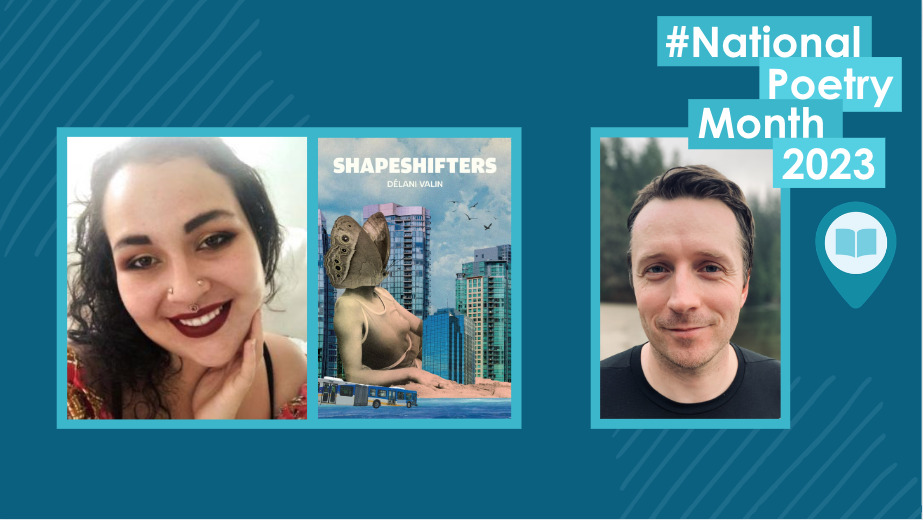

Délani Valin is neurodivergent and Métis with Nehiyaw, Saulteaux, French-Canadian, and Czech ancestry. She studies for her master’s in professional communications at Royal Roads University, and has a Bachelor of Arts in Creative Writing from Vancouver Island University. Her poetry has been awarded The Malahat Review’s Long Poem Prize and subTerrain’s Lush Triumphant Award. She is on the editorial board of Room and The Malahat Review, and lives on traditional and unceded Snuneymuxw territory (Nanaimo, BC).

Rob Taylor’s fourth poetry collection, Strangers¸ was published by Biblioasis in 2021. He lives with his family in Port Moody, BC. You can read more of his interviews here.