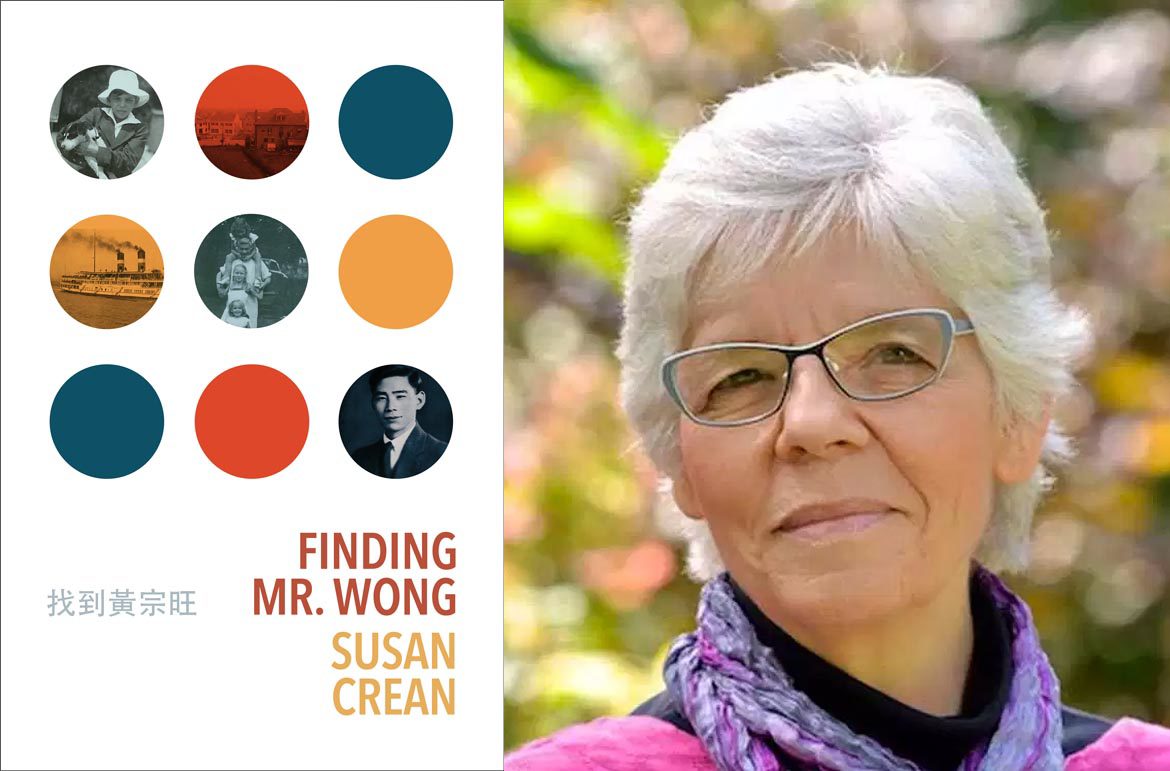

Reminiscing, Susan Crean writes, “I grew up in Mr. Wong’s kitchen …” Her memoir, Finding Mr. Wong (Talonbooks), chronicles her effort to piece together the life of the man she knew as Mr. Wong—cook and housekeeper to her Irish Canadian family for two generations.

This is your first memoir. What was the impetus for the book?

It was Wong himself, really. He was a remarkable man, even if his life was ordinary. For, as the director of the County Archives in Taishan* carefully explained to me when I paid him a visit, Mr. Wong was not a consequential figure, so I was not going to find any information about him in the archives.

As it happened, I was at the archives at the suggestion of the vice-mayor of the county town who’d sent a car round to squire me over for the meeting. I had no expectation of finding anything about Wong—talk about needles in haystacks—so I instead set about interviewing the director about the early migrations from the region, when young men left by the thousands never to return. It was well understood that leaving was a line you could only cross once. In those days emigration was outlawed on pain of beheading, so there was no going back.

“Lacking the information, there was no way to write a standard biography. Or even a fake one. Fiction was not an option as I did not want to bury the real story. Or the real man.”

The director was gracious, but the word “inconsequential” stuck in my craw. No one who’d ever met Wong would describe him that way. Though he arrived in Canada as a 16-year-old orphan with no education, he’d had an uncle who paid his passage, and gave him work when he arrived in Vancouver. Once his debt was paid, he had migrated to Toronto where he got work as a domestic cook. He was talented, and quickly acquired a reputation. His admirers included, first and foremost, my grandfather who’d hired him in 1928. Having just moved his family from a small duplex into a large house, Gramp was looking for a housekeeper as well as a cook. He hired Wong and got both. So it was that my siblings and I grew up in Wong’s kitchen. Wong taught us string games, how to ride bicycles, and most importantly, how to respect our elders. He orchestrated birthday celebrations, invented a long list of desserts that employed maple syrup—including his angel maple bomb cake—and was famous in the neighbourhood for the May 24 fireworks extravaganza he hosted each year in the back garden. He looked out for Gran and continued to spoil us long after Gramp died, staying on in the job into the sixties.

Though he was known for his culinary skills, Mr. Wong was consulted for advice on many subjects. By adults as well as children. His circle of admirers included school teachers, firefighters, the folks over at Longo’s, the Anglican Bishop of Toronto, the Silverwoods Dairy delivery man (and his horse), and kids from all over, their parents, and their pets. When he retired in 1966, Wong moved to Chinatown where we continued our weekly visits, and where he died at the age of 75 in 1970.

As a writer, I’ve not engaged with memoir, though I have written a good deal of first-person journalism. The Laughing One relied on it, although it is usually described as a biography of Emily Carr. The subtitle, which the publisher insisted on, was “A Journey to Emily Carr.” Indeed the book does focus on biography, but there is a good deal of history, philosophy, and travel writing as well. Several Carr biographies already existed when I began the book, and their existence freed me to recreate encounters and events, and otherwise play with convention. Because the basic information on Carr was available, it didn’t need repeating.

Why memoir, now? For the simple reason that writing about Wong required it. Lacking the information, there was no way to write a standard biography. Or even a fake one. Fiction was not an option as I did not want to bury the real story. Or the real man.

*Taishan is the county in Guangdong province, China, where Mr. Wong was born and where the vast majority of early Chinese immigrants came from. Taishanese was the first lingua franca of Canada’s Chinatowns.

You’ve primarily (or solely) written non-fiction. What are the key qualities you seek to include in a book as the author?

Clarity above all. Clarity of purpose, of argument, and of expression in relation to both the intellectual work and the imaginative work. The content as well as the writing. To me, it comes down to the effort to understand something, and then to communicate what’s been learned or experienced. When you are writing about real people and real events, clarity means accuracy, and not just factual accuracy. Accuracy in describing how things work, how people work. It comes together through empathy—empathy for the protagonists on one hand, and for readers on the other. The story and its aftermath. I think of it as a match-making of minds.

You’ve been an activist for many years, and your criticism of Canadian immigration laws is unambiguous in this book. Can you tell me more about your thoughts or impressions on this, or perhaps your research and what you sought to depict or discover?

Immigration law is not my beat, but it is part of Mr. Wong’s story. Sid Chow Tan tells me that only 44 Chinese immigrants came into Canada legally between 1923 when the Chinese Immigration Act banned Chinese immigration outright, and 1947 when the Act was repealed after Canada became a signatory to the UN Charter of Human Rights. [Canada] had originally welcomed the Chinese as the cheap labour that would deliver the transcontinental railway promised to British Columbia when it joined Confederation in 1871. And Chinese railway workers did indeed blast a way through the Rocky and Coastal mountains, some 600 of them losing their lives in the process.

Once the CPR was completed, though, Canada moved to prevent them from staying. The original 1885 legislation levied a $50 head tax on anyone who wanted to remain. This was repeatedly raised—reaching a crushing $500 by 1903, which could have purchased two commercial lots in downtown Vancouver at the time. It didn’t deter the Chinese. Moreover, the tax brought $23 million into the federal treasury. Close enough to the $25 million the government contributed to the building of the railroad to legitimately say the Chinese not only built it, but paid for it. Sid’s point shines a light on the obvious—that vast numbers came in as “paper sons” on borrowed documents. (I should note, by the way, that the law didn’t only apply to Chinese immigrants from China, but ethnic Chinese from other countries.)

The building of the railway is one of Canada’s foundation stories yet the Chinese contribution isn’t well-known. We don’t often acknowledge that Canada was founded on racist immigration policies that targeted specific peoples for openly discriminatory treatment. These practices lasted well into the twentieth century and were alive and well when Wong Dong Wong arrived in 1911. He remained here 55 years before becoming a citizen, working for over half a century with no permanent status. Or the right to vote.

I appreciated the information about Chinese culture, language, and naming conventions, especially how you sought to stay true to the time. What kind of research did you do to include these details?

I don’t read or write Chinese, and can barely tell the difference between Mandarin and Cantonese when spoken, so I could never have written the book on my own. I had a research assistant and translator here (Shan Qiao) and in China (Leung Xiaomei). Xiaomei accompanied me on my initial trip to Taishan in 2010. I also had the help of Howe Chan in Richmond, BC, and Chuck C.C. Wong at the Wong’s Association in Toronto. Chuck Wong is a retired university librarian, and Howe Chan a serious history buff who led a group of his relatives to China in 2014, agreeing to include me. As a result of that trip, and our visit to Shui Doi, Howe became convinced his mother was related to Mr. Wong. He spent hours poring over the handwritten family genealogy book we were shown in the village, piecing together where Wong’s place would be in the official family tree, comparing it to his own. Finally, he concluded she was a younger cousin of his. “She would have called Mr. Wong ‘Uncle,'” he tells me.

For written Chinese—there is Mandarin, Cantonese, and Toishanese in Finding Mr. Wong (the dialect spoken in Taishan)—I turned to English-speaking writers for guidance. Arlene Chan, Paul Yee, and Larry Wong in particular. All have written about Chinese communities, spoke with me more than once, and read the manuscript. In other words, I had help and advice from the beginning. Starting with professor emeritus David Chuenyan Lai, and poets Rita Wong and Fred Wah, and including community activists like Sid Chow Tan and Todd Wong. I did find Wong’s name in the Chinese Times which published community news, including lists of people doing community work, serving on committees, making donations in the 1920s and 30s. Until that happened, it had not occurred to me I might find something on the record. And when I set off for Taishan, I’d no inkling that I’d find Wong there either. Certainly nothing official. Certainly not 100 years after he left and 50 years since after he lost contact with people in the village. What were the odds?

I visited his home village anyway. It’s called Shui Doi, and we made sure to visit the District director first. There we met Wong JinHua, the affable village head, and arranged for him to show us around when we visited a few days later. He pointed out where Wong’s parents’ house once stood and introduced us to the grandson of Wong YeeWoen, the younger brother of Wong’s father who had brought him to Canada. Wong YeeWoen dug out the family genealogy book, showed us where Wong’s name. The few facts I had turned out to be accurate. Wong’s father died before he was born, his mother died when he was 16 months, his grandfather when he was two. There were no siblings and just one remaining uncle. Not much to go on.

This book is as much about your family as it is about Mr. Wong, and the descriptions of your Granny and Wong’s relationship has such emotional depth. What type of research did you do into your family history? Were your family members open and cooperative?

I did little research on the Crean family per se as it is fairly well documented. I did visit the areas in Ireland where my great-grandfather was born and his family lived until the 1840s. Similarly, I visited Mr. Wong’s home village in Taishan and met the descendants of the uncle who brought him to Canada in 1911. In both cases, I went to discover what they each left when they came to Canada. This required two things, that I experience the two places, and read the histories of the two countries. What was the situation in the China Mr. Wong left in 1911? What was happening in Ireland when my great-grandfather up and left—joined the British married, married a Protestant, and left. Those investigations took four years and three major trips, which is why the book took eight years to write.

I have three siblings so I was writing about a shared history. I have to say that all three were generous to a fault, offering their own research and ideas, reading and critiquing the manuscript. Wong was instrumental in the lives of all of us, of course. Someone who beat Santa when it came to special treats and outdid Gran in words of wisdom. And talk about fixers! All of us are endlessly happy talking about him, and so the project brought him back for us. There was no disagreement about what I wrote, only more stories.

“Wong was instrumental in the lives of [my family]. … All of us are endlessly happy talking about him, and so the project brought him back for us. There was no disagreement about what I wrote, only more stories.”

The note you included at the beginning indicated that parts of the book have recreated known events while some are fictionalized. How did you seek to balance the truth with weaving a compelling story and narrative for the reader?

To restate something we all know, fiction is not all invention nor is nonfiction is all facts. Writing comes in many guises, propelled by a diversity of purpose. Genre to me is not about judging the “truthfulness” of a work. So I don’t use the term fictionalize as code for “untrue” or “made-up,” rather I see (and use) it as a literary device. And I do not see my work as an exercise in balancing truth and untruth. So I don’t really accept the premise of the question. I realize some people are genuinely perplexed by the idea of fictionalizing history, even though that is what historians generally do—construct a story from the evidence, the known facts, and the testimony. That is why histories vary, why the narrations differ and sometimes contradict each other.

What is the hardest part or section to write in Finding Mr. Wong, and why was it difficult?

The entire book, actually. I’ve been a journalist all my life, and have often written in the first person. But I have rarely written about myself, or my life growing up in Forest Hill with servants. So I had to find a way to do that, and the voice. The book took the shape it did because I wanted to place Mr. Wong on a stage large enough to include history, philosophy, political analysis, personal history, and travel chronicles. Now an entire book has been written about him, I think I will be sending a copy to the Director of the Taishan Archives.

I do not spend time thinking about genre, but I feel we do our literature a disservice separating them as if fiction and nonfiction were wholly distinct and different. It seems to be an Anglo-American obsession that you don’t find elsewhere, or in other languages. The book that inspired me most in writing the Carr book was Henri-Lévy Beaulieu’s three-volume life of Herman Mellville, Monsieur Melville (1978). As the writer of the TV drama Race du Monde, Beaulieu began the book by calling a meeting of the show’s characters to announce that he was taking a leave of absence to write a book. A sort of memoir. They responded by letting him know they didn’t need him and could carry on without him just fine.

Which book(s) have you reread most in your life?

First and foremost, Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit. (And although it may not count, I will never forget Timothy Findley reading it in Convocation Hall at U of T.) Others I returned to: Henri Pirenne’s Mohammed and Charlemagne, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Franz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth, Ursula K LeGuin’s Woman on the Edge of Time, and Simone de Beauvoir’s Une Mort très Douce.

What are you reading?

I am reading the ambitious and absorbing anthology about water edited by Dorothy Christian and Rita Wong called Downstream — Reimagining Water. I am doing this with a small group of friends who are artists and, like me, enjoy reading texts about theory and art, politics and ideas. And then talking about it. The lines of investigation in the collection mostly conceptualize water as elemental and at the same time as spiritually and imaginatively compelling. What I take away from the discussion, are ideas that feed my own intimate relationship with water as a life-long swimmer.

What are you currently working on / working on next?

A series of personal essays about artists I have know as friends called “Sleeping in the Studio.” It begins with a piece on artist Jack Chambers titled “Carrots for Breakfast” (published in the AGO’s 2011 exhibition) and will include photographer Michel Lambeth, violist Rivka Golani, nature writer Fred Bodsworth, artists Alex Janvier and Jacques Oulé, among others.

Susan Crean was born and raised in Vancouver, Ontario, and is of Scots-Irish descent. Her articles and essays have appeared in magazines and newspapers across Canada, and she is the author of seven books; the first, Who’s Afraid of Canadian Culture, appeared in 1976. Her most recent book, The Laughing One: A Journey to Emily Carr, was nominated for a Governor General’s Award and won the Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize (BC Book Prizes) in 2002. Crean currently lives in Toronto.

Susan will be launching Finding Mr. Wong in Vancouver on October 11 at Dr. Sun-Yet Sen Gardens.