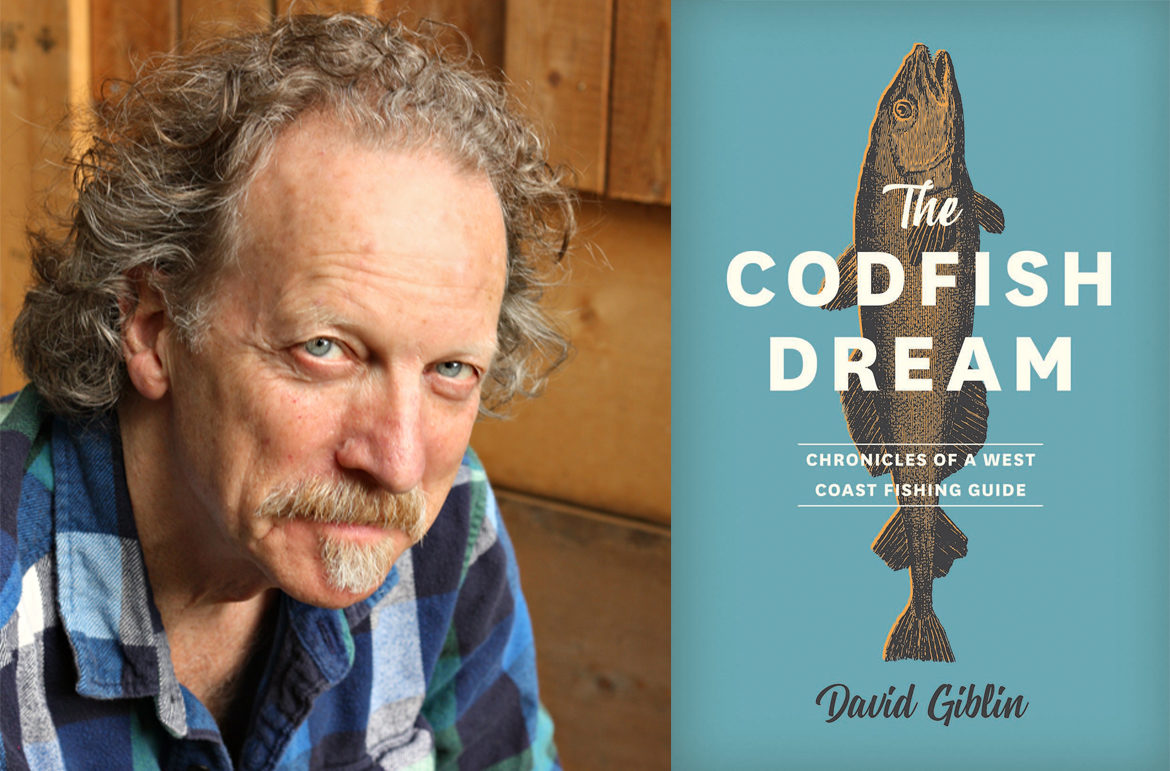

After spending fifteen years as a fishing guide on the BC coast, David Giblin decided that the offbeat people and places he’d encountered during that colourful period in his life had to be preserved. The following excerpt is from The Codfish Dream: Chronicles of a West Coast Fishing Guide by David Giblin (Heritage House).

I had taken Morris Goldfarb fishing before. Last summer Morris arrived during a particularly hot period of fishing. People were catching fish on every tide, and a number of big spring salmon over thirty pounds were already weighed in at the lodge. Fish that big are called tyee, a word used by the local Indigenous people that means “a damn big fish,” or something to that effect. You could feel the excitement in the air; everyone, guides included, wanted to catch the next tyee.

Along with the thrill of playing and landing such a large and powerful salmon on the light tackle we used, there was a certain status involved. Some people spent years and thousands of dollars without ever coming close to catching one. Having the experience put you in a select club. The resorts awarded prizes, special sweatshirts, and commemorative pins. Bottles of expensive champagne got popped open, and the guide responsible might be tipped hundreds of dollars.

Over the course of the whole summer, during hundreds of hours of fishing, a guide might experience a tyee celebration only two or three times. Each time a guide dropped a piece of bait in the water he did it with great care; it might be the one that caught the next tyee.

Each time a guide dropped a piece of bait in the water he did it with great care; it might be the one that caught the next tyee.

Morris, however, couldn’t have cared less. I don’t think he even knew what a tyee was. A speech he had to give at a business meeting the following week commanded all of his attention. He had come to Stuart Island to relax and memorize his presentation. Somehow he found being out in the rapids in the middle of a busy fishing hole helped his concentration.

He sat in the boat, rod jammed between his knees, the speech open on his lap, mumbling to himself as he memorized his lines. If I wanted him to let some more line out or reel in to check his bait, first I had to get his attention. Each time he turned to his speech he was transported out of my boat to a podium somewhere, holding an audience of his business peers enthralled with his insight and wit. For Morris, this prospect was an experience far above any mere fishing action.

To make matters worse for me, every time a fish was caught near us I had to watch the lucky fisherman play his catch around the hole or out into the tide. There was no point trying to fish seriously; that took a certain amount of teamwork and co-operation. We were fishing a spot known as the Second Hole, a large back eddy that moved the boats around it as though they were on a giant carousel. The main current flowed down the centre of the channel. The water it displaced pushed up against the shores of Stuart Island in a sweeping, circular fashion. The guides would line up at the top of the circle, ride the faster water down the outside edge, head the bow of their boats in toward the shore, and ride the slower moving back currents to the top of the hole again. We would have to watch the depth as we circled in order to avoid the rocks and reefs on the bottom. The salmon hid among these rocky places and waited for their food to come to them.

Morris, lost in his speech, couldn’t be interrupted. I hung around near the top of the back eddy so as not to interfere with any of the more serious fishermen. The part of the hole we were at collected a great deal of driftwood and debris. It kept bumping into the line where it entered the water. At one point my line touched a small piece of bark. At the same time, the rod tip twitched, then dipped toward the water. Morris paid no attention and continued to mumble to himself. I asked him to reel in his line.

“Why?” he asked. “Do you think I need to?”

“Well, I think you might have a fish on. If you reel up, we’ll find out.”

“I don’t feel anything there. Wasn’t it just the line bumping into that piece of wood?”

Morris didn’t want to bother with the interruption.

“Morris, as a favour to me, just reel up and see what happens.”

“Are you sure? There’s nothing there. If a fish was there, I’d be able to feel it, wouldn’t I? It was only that piece of wood.”

Morris was growing impatient with me. I tried a different approach.

“Look, Morris, it’s about time we changed bait anyway. Just bring the line in for me.”

Morris sighed; he was a man beset by unreasonable people always making unreasonable demands on his time and patience.

“I really think it was only that piece of wood. The bait should still be okay, shouldn’t it? The wood couldn’t hit the bait, could it?”

We had been dragging the same herring around for at least an hour. It surprised me a fish would even bite it. Yet, from the way the line was acting, there was definitely something there. Probably just a rock cod, I thought.

Morris put down his papers on the empty seat next to him and started to reel the line in. He had turned the handle three or four times when the line suddenly started to peel off in the other direction. Morris clucked in exasperation.

“How the hell am I supposed to get the line in if the reel isn’t working properly?”

He gave me a dark stare as if the problem were my faulty equipment. The line was leaving his reel by now at an alarming pace.

“It’s supposed to do that, Morris. You’ve got a fish on.”

He still regarded me with suspicion, but the line was now making the reel scream as it left. It was a salmon all right, and judging by the way the line was running, it was a big one.

Like any good fishing story, wherein the fish seem to grow faster after they are dead, the forty-seven interconnected narratives in what eventually became The Codfish Dream took on a life of their own. The result is a series of hilarious, strange, keenly observed, true (or mostly true) stories of Giblin’s experiences. These whimisical tales are held together by a thread of international intrigue that affects everyone in the small community of Stuart Island over one eventful summer, when FBI agents visit the island to investigate insider trading. The Codfish Dream is an unforgettable book imbued with an undeniable sense of place and time.

David Giblin worked for fifteen years as a salmon fishing guide at Stuart Island, roughly 50 kilometres east of Campbell River—a fertile environment for the incubation of great fishing stories. As an unpublished manuscript, The Codfish Dream was a finalist in the Cedric Literary Awards in the creative non-fiction category. Also a visual artist, Giblin lives in Cobble Hill, on Vancouver Island.

One reply on “Life as a West Coast fishing guide”

[…] Life as a West Coast fishing guide […]