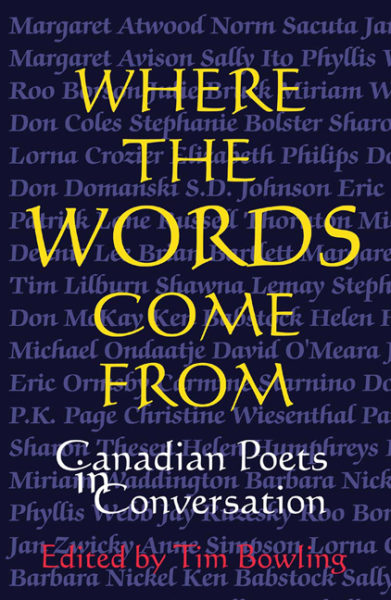

In 2002, Nightwood published Where the Words Come From: Canadian Poets in Conversation, a successful first-of-its-kind collection of interviews with literary luminaries like Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Margaret Avison, Patrick Lane, Lorna Crozier, and P.K. Page, conducted by emerging poets of the day.

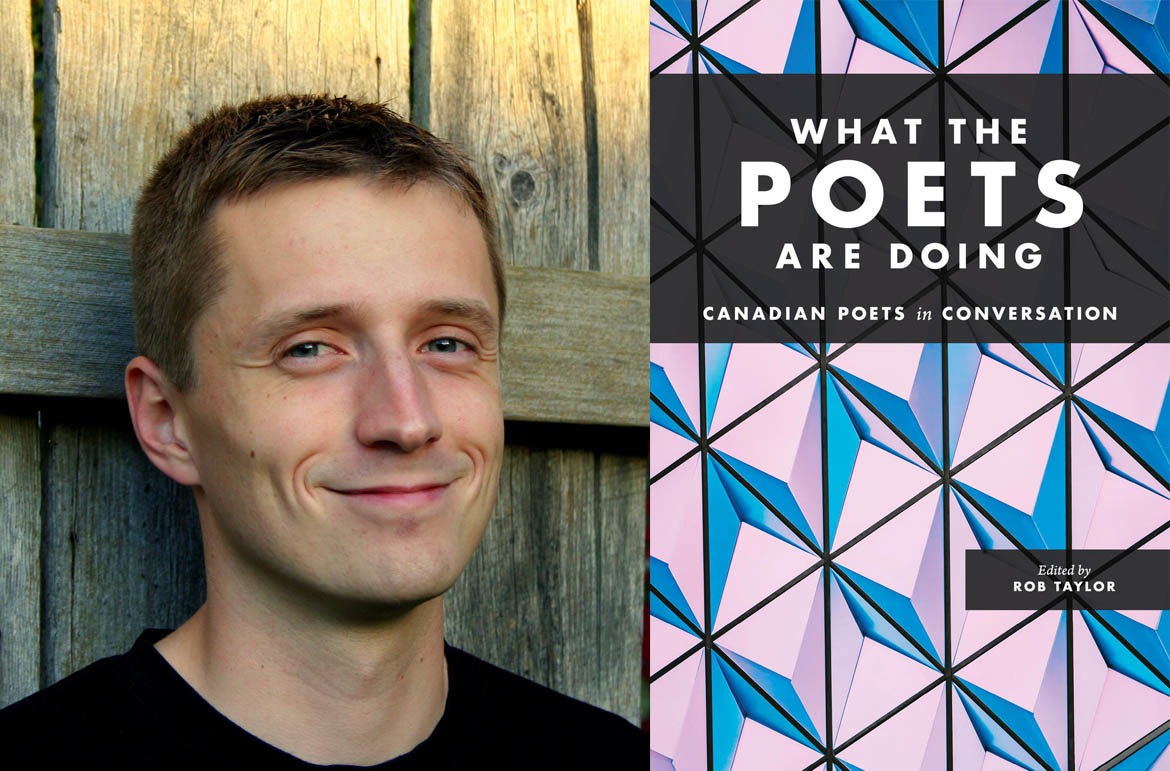

Sixteen years later, What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions) brings together two younger generations of poets to engage in conversations with their peers on modern-day poetics, politics and more.

In an exclusive interview, editor and poet-wrangler Rob Taylor illuminates what the poets are actually doing.

You attribute the idea for this book to Where the Words Come From (Nightwood Editions, 2002) in which up-and-coming Canadian poets interviewed their esteemed older colleagues. Why did you feel the need for a sequel or updated version?

Where the Words Come From was the first book of its kind, and we’ve had nothing like it published in the intervening 16 years. During that time four Alvin and the Chipmunk movies and six Nickelback albums have been released. I think one sequel to Where the Words Come From is not too much to ask.

More seriously, though, the Canadian poetry landscape has changed significantly since 2002. New poets, of course, with a more diverse range of backgrounds, perspectives, styles, and politics. New stories and new ways of talking about them.

More than anything, though, I just really love the concept behind Where the Words Come From—two people discussing an art they care about deeply, and all of us get to listen in from the corner of the room. A podcast on the page! I wanted to bring that idea forward for another generation.

What was it about Where the Words Come From that stuck with you as a reader? What do you hope from What the Poets Are Doing sticks with readers?

What stuck with me from the first book was a feeling. You know that feeling you get from the books that have been truly important to you? That it shaped you in some way. That even after all these years, it’s still in there, in the cobbled mess of you, holding up everything around it?

Where the Words Come From came out when I was 19 and only just starting to find my way to being a poet (a long path which I am still walking). But how does one “find their way to being a poet”? Through poems, of course, but also other means—literary readings, critical essays, social gatherings between writers. I like to think of Where the Words Come From as having been a combination of those last three things in book form, which was vital for me as I didn’t know any writers personally, and didn’t (and don’t) like actual parties. In just being there, in the room of that book with all those writers, I got a sense of what a life in writing might be.

I hope this new book can serve the same role for prospective writers and readers alike: a welcoming into this strange world of writerly concerns, habits, fears, jokes, and acts of faith. And for those already fully committed to poetry, I hope it serves to reinvigorate, to take them back to the source, that first feeling.

“One of the joys of this book is experiencing how the lives and perspectives of the poets intertwine and complement one another, not just in individual conversations but across them.”

How did you select the poets to include, and how did you pair them up?

Oh, I had a list of about 150 beloved Canadian poets, but the publisher thought I should whittle it down a bit! It was a tough process, coming up with a list of “established” poets, but working with Silas White at Nightwood, we got it down to the list you see here (as I say in the introduction, the book could easily have been many times larger and just as strong, the depth of talent in this country being what it is).

The only overriding selection criteria was that the poets needed to be people who had interesting things to say about the art. I reached out to the poets about the project and offered them one or a few names of possible partners with whom I thought they’d spark a vibrant conversation. I also offered them the opportunity to pick someone from “off the board,” which a couple of them took me up on.

Why did you decide to also include poem excerpts with the interviews?

This goes back to my answer about what stuck with me from Where the Words Come From. That book felt like a one-stop shop for all things poetry, except it was missing the poems! I thought adding one poem by each poet would crystallize all the talking-about-poetry that the poets were doing around something tangible, like a germ of dust gathering a snowflake.

I think it’s also a pleasing experience to be reading a conversation about a particular poem and just as you start thinking “I should go look that poem up”—whammo, there it is on the next page. Some of the poems prove vital to the conversations around them, and the way Elizabeth Bachinsky and Kayla Czaga slip a poem into their conversation is particularly delightful.

The other reason for including the poems was a recognition that some of these poets, especially the younger ones, might be unfamiliar to readers. The first book featured the CanLit Hall of Fame (Atwood, Ondaatje, etc), with most of the conversations functioning (understandably) more as one-way interviews, so the relative anonymity of the younger poets wasn’t as great a concern. In this book, I wanted the spotlight to be shared between the two poets evenly, and that meant finding ways to balance things out. So everyone gets one poem to help establish their voice and style for the reader.

“The through-line is always there: writers carefully considering language, how it manifests in poems, and what use it can (or can’t) serve in the wider world.”

It’s interesting that you differentiate between an interview and a conversation. Why did you make this distinction, and what do you think the idea of conversations instead of interviews contributes to the book as a whole?

As I was touching on in my last answer, conversations go both ways while interviews go one way. Depending on the nature (and “status”) of the participants, what are meant to be conversations can sometimes turn into interviews, and vice-versa. In this case, I made clear to the participants from the beginning that they were to both contribute equally; to interview one another simultaneously, in a sense. No one had a problem with that, which I think is a sign that attitudes around literary canons and hierarchies are (thankfully) changing.

I believe thinking about the interviews as “conversations” brought more personal investment into each question a poet offered their partner, as they fully expected that question would be returned to them. I think most interviewers ask questions that they are thinking about themselves, but they rarely get a chance to answer them—so this opened up that space.

Likewise, I think the nature of the conversations allowed the poets to intuitively navigate to subjects of shared interest or concern, instead of being dictated by a pre-prepared list of questions or expectations.

In the introduction, you state that “while the book does adhere to the structure of pairing established and up-and-coming poets, the qualifications for who fits in which category were amorphous and largely ignored when finalizing a pairing.” What key elements or qualities did you seek to balance in pairing the conversationalists?

The poets were paired for all sorts of reasons. Some wrote in similar styles. or on similar themes, or in some unexpected way had overlapping practices. Sue Goyette and Linda Besner, as well as Russell Thornton and Phoebe Wang, stand out for me in this way. Though most were strangers, some were friends or had been colleagues on a project. And Sue Sinclair and Nick Thran, who wrote our afterword, are married and have a child, so a friendship and a project at once. Two pairs didn’t know each other well, but shared a common childhood home (Armand Garnet Ruffo and Liz Howard; Tim Bowling and Raoul Fernandes). Etc. Etc.

One of the joys of this book is experiencing how the lives and perspectives of the poets intertwine and complement one another, not just in individual conversations but across them.

What parameters did you set for the poets’ conversations to ensure each piece fit into the whole? How did you develop the project to create a cohesive whole?

This is something I thought about a lot in the lead-up to the conversations taking place and returned to in the editing process. For Where the Words Come From, editor Tim Bowling had all the “emerging” poets ask three set questions to their partners, as part of the larger interviews. I considered this but decided against it—the range of possible subject matter for poets these days is so wide open that I didn’t want to restrict conversations in that way (even in 2002 some of the poets chafed at the requirement!). In place of those questions, I requested the poems, alongside an encouragement to discuss the poems in some way but also to move out from them to larger themes. I thought of this as a way to bring a shared structural element to the conversations, while still allowing the conversations to be about whatever the poets’ inclinations dictated.

It’s tricky: we all desire some level of unity in a project like this, but what do we lose in the process? More often than not, bringing new voices, diverse voices, “outside” voices into the conversation to change the status quo. I wanted to leave space for those voices, while still keeping things tethered together in some way. In hindsight, I shouldn’t have been concerned. The through-line is always there: writers carefully considering language, how it manifests in poems, and what use it can (or can’t) serve in the wider world.

“The book lives for me as one big illumination about the range and depth of work (and thought) being undertaken by poets in this country, and about what will come next.”

You compiled this book on a very tight timeline. What was the most difficult part of this process?

When I read this question, I laughed, then wept quietly for a couple minutes, then went back to laughing. It was wild (well, by publishing standards). Imagine a Formula One race but with frantic emails instead of hairpin curves and late-night editing sessions instead of pit stops (it’s soon to be a spectator sport, I’m sure).

It was important to me that the book come together on a tighter timeline than usual because, well, have you seen the world? The political landscape—and the poetry landscape, for that matter—are changing so rapidly that even something written a month ago can seem dated. So we didn’t want the conversations growing stale for over a year, as is the norm. I think we all knew what we were getting ourselves into (the publisher most of all, then the poets, then little ol’ clueless me).

The most difficult part? Oh, it was a group of poets, being managed by another poet. You can imagine. It was kind of like one of those cat cafés, except the customers and employees were cats too and there was coffee and food spilled everywhere. Great credit goes to Nightwood’s poetry and fiction editor (and non-cat), Amber McMillan, for tidying up our mess.

As the editor, did you revise or polish the conversations much, or are they verbatim?

They have certainly been edited, but mostly for clarity, not content. The odd, natural ways a conversation moves have been maintained as much as possible. I didn’t want the reader to sense an editor in the room with them, rearranging the furniture.

Did you discover anything surprising or shocking while reading the conversations?

Shocking, no. Surprising, constantly (in the best kinds of ways). Dionne Brand spies on conversations in the middle of the night, Marilyn Dumont traces her roots back to the Hudson’s Bay Company, Elizabeth Bachinsky tracks down Sue Sinclair in the woods, Sue Goyette stalks an agave plant, etc. But those are just easy-to-summarize surprises. The best are the subtler ones, the ones that sneak up on you in ways you can’t ever really explain later. You’re just going to have to read the thing.

What was one of the most illuminating or inspiring conversations for you, and why?

Nope, not falling for this trick! I treasure all my darlings equally. In all honesty, the book lives for me as one big illumination about the range and depth of work (and thought) being undertaken by poets in this country, and about what will come next.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best Canadian Poetry in English (Biblioasis, 2019). In 2015, Rob received the City of Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for the Literary Arts, as an emerging artist. He lives in Port Moody, BC with his wife and son.

What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation is a collection of conversations between established and up-and-coming poets focusing on the role of poetry and poets in the twenty-first century.

Poets in Conversation:

- Steven Heighton and Ben Ladouceur

- Armand Garnet Ruffo and Liz Howard

- Sina Queyras and Canisia Lubrin

- Dionne Brand and Souvankham Thammavongsa

- Marilyn Dumont and Katherena Vermette

- Sue Goyette and Linda Besner

- Karen Solie and Amanda Jernigan

- Russell Thornton and Phoebe Wang

- Tim Bowling and Raoul Fernandes

- Elizabeth Bachinsky and Kayla Czaga

- Afterword co-written by Nick Thran and Sue Sinclair

The collection will be launched in Victoria on Saturday, November 17, 2018, and then in Vancouver on Sunday, November 18, 2018.

One reply on “What are those Canadian poets doing, Rob Taylor?”

I’m here to tell the poets that they are doing a wonderful job. They know what to do with the small things as well and this will not be the case for any of us too. It will be too hard for me.