The following interview is the sixth installment of a nine-part series of conversations with BC poets about their new poetry collections. New interviews will be posted every Tuesday and Thursday throughout April for National Poetry Month 2019. All interviews were conducted by Rob Taylor, editor of the recent anthology What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions).

Final Vocabulary – George Stanley

‘Life is about other people.’

Peter Weber

‘I is an other.’

Rimbaud

Do what you’re here for.

Reprinted with permission from Some End/West Broadway by George Bowering and George Stanley (New Star Books, 2018).

This is part two of this interview.

Read part 1 now here.

George Stanley (GS), in the 2014 Capilano Review issue devoted to George Bowering (GB), “Bowering’s Books,” you wrote about what was then GB’s most recent collection, Teeth (Mansfield Press, 2013). You talked about the poems where Bowering takes us on a trip: “Like a trip, [GB’s poem] goes somewhere. It goes more than one place, it seems to want to go places.”

This quote reminded me as much of your Vancouver poems/books as anything (we’re on the bus, going places, but we’re also going so many other places, too). In what ways do you think GB, through his friendship and/or his poems, has influenced your own writing, or the way you think about it?

GS: Some poems of George’s have an inherent desire to move on. In that review/essay I contrast his poetry with the kind of poetry that is constantly looking back at itself and justifying itself. His wants to move somewhere else.

I don’t think that George’s writing has had any particular influence on my writing, but what drew me to him in 1971 was his intelligence and his warmth. We had no difficulty understanding each other. It was really an instant kind of friendship. All through our years of friendship, he’s really instructed me in Canadian literature. It often turned out that the poets that I liked the best were the poets that he’d always seen were the best, for example, Margaret Avison or John Newlove.

GB, how do you think GS’ writing and/or friendship have affected your writing life?

GB: He is a real friend. It is what one would have asked of life—to have a friend who works at the art, who studies poetry, who has read Euripides and Anna Akhmatova and John Newlove. I may not steal his tropes (though he should not be unwary), but I will work better at the vocation knowing that he is in my life.

GB, in your half of the book, Some End (New Star Books), there is a tribute to Peter Culley. In it, you write movingly about how older poets (and readers) need what younger poets bring them “out of the dark.” The poem is all the more moving knowing that Peter Culley died of his heart attack only 11 days before you had your cardiac arrest. You speak in many other places (and poems) about your peers and elders, but could you talk a bit about some younger writers who have influenced your writing? Or just some of your favourites (on the page or off)?

It seems as if the longer I stay here, the more younger poets there are.

—George Bowering

GB: It seems as if the longer I stay here, the more younger poets there are. And there are so many now. I have always paid attention to the young writers, and now I am talking about those, say, who are 20 to 50 years younger. I recently published an essay about Vancouver poets, the oldest being Earle Birney and the youngest Ryan Knighton, whom I first knew when he was around 19. When I read those words now, “We call it light,/we who need/ what these younger/ bring, at their cost/ back out of the dark,” I could have been writing about Ryan, who is blind, though really, I am struck now by how right those words and their placement are—but I could not lay out in prose their meaning. But you know, when I name some of my favourite younger poets you will say that they are your elders, eh? I mean come on—Erin Mouré teaches me and so does Oana Avasilichioaei.

How about you, GS?

GS: My intuition is that I assume that I have learned something from younger writers but I can’t know what it is in the way that I would know what I’ve learned from older writers.

Why do you think that is?

GS: I guess it’s something about the nature of time.

As we consider younger writers, could you each speak a bit about the role of mentorship in your life? GB, you’ve written often about the importance of Al Purdy and the A-frame in your development as a writer (your wife, Jean Baird, chairs the Al Purdy A-frame Association). Who were the writers whose friendship or guidance shaped you the most, and how do you find yourself “passing it on” to other writers? What role does the A-frame play in that process?

GB: I keep hearing about mentoring, mainly from people at the universities. I have never got comfortable about the word, though people often accuse me of being a mentor to lots of younger writers. I don’t know. Is it mentoring if a poet writes about poetry and a tyro reads such writing and says that sounds right? Of even if an older poet’s method of composition persuades the younger to work from that stem? If so, I have been mentored by William Carlos Williams, whom I never met, and Robert Duncan, D.G. Jones, Gilbert Sorrentino, H.D., Ezra Pound, and Margaret Avison. When I was starting up I showed a short poem to Allen Ginsberg. He said to get rid of all the little function words, the ones the 18th-century poets used to fill out their iambic. I did, and he was right. One of the best tips I ever got. I like, if that is what you are talking about, pointing out something a poet has done nicely. I did that with Patrick Lane a couple of weeks before he left us. But I have never done that at the A-Frame. I went there to be with, not to learn.

GS: One thing I’ll add is that mentorship was what that “Dads and Tads” group I mentioned earlier was all about. It went on for two or maybe three summers in the late 90s. Young poets like Ryan Knighton and Reg Johanson were learning from me and George and Jamie Reid as the elder poets, the “dads” of the group. As for me, my own mentors were Jack Spicer and Robert Duncan.

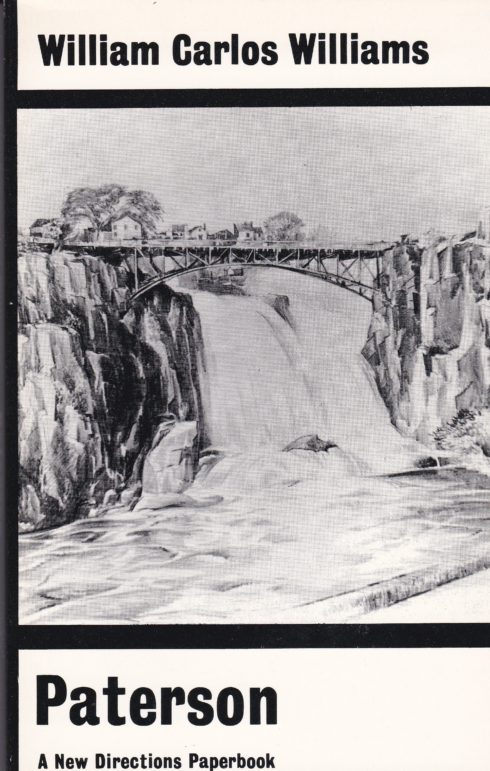

GB, in your answer you mentioned W.C. Williams as a mentor-in-writing. He seems like a significant poet in both of your lives – GB has written in the past about the important role The Desert Music played in his development as a writer (and then there’s the whole “icebox” thing in Some End), and it’s hard to read your series of books and poems about Vancouver, GS, and not think of Williams’ Paterson (in “Letter to George Bowering” you call it your “Paterson pastiche”). What do you think you learned from Williams?

GS: Williams, of course, is the progenitor of all of us modern poets, not just me and George but all the poets in The New American Poetry dating from about 1960. To me there are three essential factors of modern writing: one is ordinary language, one is free-form or vers libra, and one is precise states of emotion, and they’re all in Williams.

I was never influenced to write anything by a particular poem of Williams’ until I read Paterson, the first book of Paterson particularly, and that gave me the idea of writing a long poem about Vancouver.

Was it just the idea of writing about a town, or something about how Williams wrote his poem?

GS: The way that Williams wrote that poem, in that there would be verse and then there would be long prose passages. That was a kind of “mixed style” that I adopted. But at the very beginning of that poem, I distance myself from Williams because Williams identified himself with the city of Paterson and I couldn’t identify myself with the city of Vancouver. I wrote, “this is not my city.” My city was San Francisco.

Do you still feel, after so many years, that this could never be your city?

“Somebody I’ve never met is reading me in Eastern Canada? I must be a Canadian!”

—George Stanley

GS:Oh, it is now, just like I’m now a Canadian. Fairly recently I began to refer to myself as “an American poet and a BC poet,” but I think I might as well accept the fact that I’m a Canadian poet too. I read a review in The Malahat Review of After Desire and it was written by an academic who I’d never met from Queen’s University. I thought, “Somebody I’ve never met is reading me in Eastern Canada? I must be a Canadian!”

Back in 1980, I had the idea that I could become a Canadian poet by writing poems about Terrace, because I had read poets like Margaret Avison, who wrote about Toronto, and Margaret Laurence, who wrote about a small town in Manitoba. I thought, “If I write poetry about a small-town and BC, this will make me a Canadian poet,” but that didn’t really work. I lived 15 years in Terrace and one year in Prince Rupert, so I do think of myself as a British Columbian. I found out that a lot of native-born Vancouverites never think of going to the interior. They go to Toronto but not to Kelowna.

GB, what are your thoughts on Williams’ impact on your writing?

GB: In high school I did what I thought all the kids did: read the poets we weren’t being fed in class. That’s how I got H.D., Hart Crane and William Blake, for examples. In first year at Victoria, we had that fat little anthology by Oscar Williams. There were two William Carlos Williams poems in it, one of them in the “humor” section. No professor showed me WCW. But when I found him I hung on tight—I was a kid on the road to Damascus.

Speaking of influences: we’ve mentioned Anna Akhmatova a few times already in this discussion. GS, your Akhmatova translations and poems are appearing more steadily in your recent books. You note in “Letter to George Bowering” that you “can’t get [Akhmatova’s poem] to stay put in 1944” – instead your translations often bring her to modern-day Vancouver (so your “imitation” of her poem “Our Age,” about “decline of the West,” becomes about West Point Grey, for instance). What’s going on here? Why do Akhmatova’s words move so irresistibly into your 21st-century Vancouver?

GS: I spent a few weeks in Moscow—maybe it was only about 10 days—in 1991. I met some people there and I got interested in the Russian language. I began learning to read Russian poetry, and I was drawn to Akhmahtova. She was a very modern poet for her own time. She belonged to a group called the Acmeists, “acme” being the height of realism. She’s very much a realist poet.

I connect with her because I think of myself as a realist. I used to call it simply an “aboutist,” I wrote poems that were about something. That was in reaction against Language Poetry, which turned the arrow of reference back on the poem itself. Akhmatova broke with the reigning poetic movement of the time, which was symbolism, and began writing this very precise, realistic poetry (like Marianne Moore said, “plain [language] which dogs and cats can read”).

GB: I have been hearing about her most of my poetry life, but I am ashamed to say that I have never given her many hours. I did the usual thing for people my age—I let Vladimir Mayakovsky be my Russian.

That idea of letting one person represent a country is a good lead-in to my next question. In the title poem in Some End, GB writes, on the idea of being young again: “but what about all these books? Would we / have to write them again?” Which books would be the first you’d write again (if any), and why? Which would you have represent your country?

GB: The way I read that poem is that I don’t know whether I would be able to start on such a big job. Give me another life and I will write whatever gives itself to my hard-working brain or soul. I can tell you which of my books I would not write again first. It would be How I Wrote Certain of my Books.

I’m reminded of a joke that George told when we were in Seattle. Before he started reading he said, “This is my prayer, oh Lord. If I have only one life to live I hope this is not it.”

—George Stanley

GS: I’m reminded of a joke that George told when we were in Seattle. Before he started reading he said, “This is my prayer, oh Lord. If I have only one life to live I hope this is not it.”

I would imagine if I had another life, I’d be another person, I’d write different poetry (if I wrote poetry. Maybe I wouldn’t write poems!).

If I had a chance to go back over all my work, I think right now I would cross out much more of my work than I would have even 10 years ago. I sometimes look back at a poem of mine and I think “this is really pretentious” or “this is stupid,” whereas back then I thought it was a good poem. At the same time, when I look back I know which are really good poems that I’d like to keep. I would keep a poem called “Flesh Eating Poem” and a poem called “Pompeii,” but I would probably drop a poem called “Achilles Poem,” which was an attempt to imitate Charles Olson.

Moving from one form of flattery to another (imitation to tribute), two of the most moving poems in the book – one by each of you – are tributes to Jamie Reid (“Inside Ours” and “Love”). Reid was, as you mentioned earlier, your third Dad amidst the Tads, and died in 2015. Together your two poems about him talk about the intermingling of the personal and the political, attempting to pull in some of the many elements of Reid’s writing and life. What one thing would you like unfamiliar readers to know about Reid and/or his writing?

I envied Jamie Reid. He was a beautiful skinny imp Rimbaud. If he were to kiss your cheek in the evening, you would wake up more intelligent in the morning.

—George Bowering

GS:I would say there are two things: first, that he was a poet in a radical, modernist sense. People used to criticize Jamie because of his membership in the Communist Party of Canada (Marxist-Leninist) as though he’d betrayed poetry or something like that. His identifying with communism goes back to Marx and the thinkers and poets of the 19th century. For Jamie, to be a communist was to be a modernist.

The second thing is that he had a big heart. He had so much love for people, and I remember the kind care he took for two poets in the last days of their lives: Billy Little and Goh Poh Seng.

GB: In the Tish days, I was the oldest of the five editors, and Jamie was the youngest. I knew everything there was to know about everything, of course, but I envied Jamie Reid. He was a beautiful skinny imp Rimbaud. If he were to kiss your cheek in the evening, you would wake up more intelligent in the morning. I was one of those people who regretted his years as an adherent to that goofy political outfit, but just a few years ago I saw him playing the gravedigger in a production of Hamlet. It was then I knew that I knew him.

George Bowering was born in Penticton, BC. He spent his freshman year at Victoria College, then joined the RCAF for three years, then got two degrees at UBC, then went to teach at Calgary, Sir George Williams, Simon Fraser, and three European universities. Then he retired so that he would have time to write books and so on. He is currently writing a little book in which he looks at the poetry of John Keats, Emily Brönte, Sir Philip Sidney and others.

George Stanley is the author of seven previous books, the most recent being After Desire (2013), Vancouver: A Poem (2008), and North of California St. (2014), which collects poems from three earlier, out–of–print books. Born in San Francisco and living in Canada since 1970, Stanley was the 2006 recipient of the Shelley Memorial Award from the American Poetry Society.

Rob Taylor is the author of three poetry collections, including The News (Gaspereau Press, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Rob is also the editor of What the Poets Are Doing: Canadian Poets in Conversation (Nightwood Editions, 2018) and guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best Canadian Poetry in English (Biblioasis, 2019). In 2015, Rob received the City of Vancouver’s Mayor’s Arts Award for the Literary Arts, as an emerging artist. He lives in Port Moody, BC with his wife and son.

Read more 2019 National Poetry Month features here.

One reply on “A big work presented to all: An interview with George Bowering and George Stanley (Part 2)”

[…] A big work presented to all: An interview with George Bowering and George Stanley […]