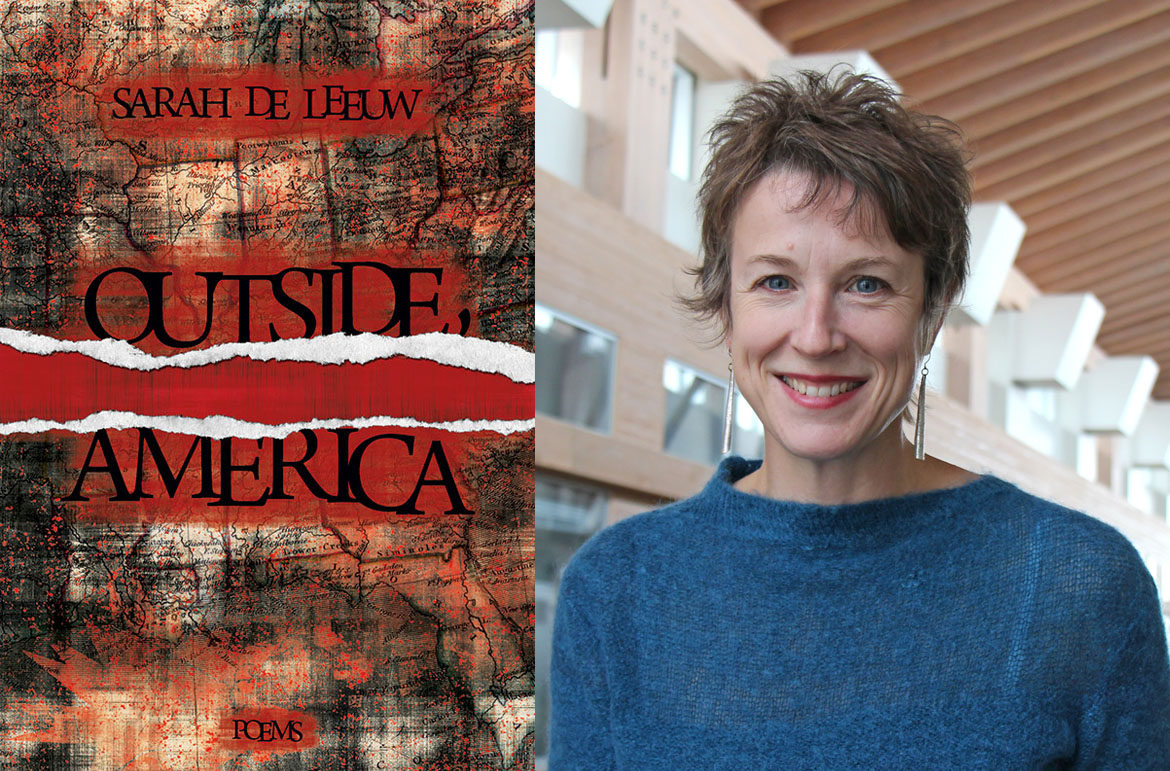

Sarah de Leeuw’s latest collection, Outside, America (Nightwood Editions) crisscrosses the Canadian/American border and makes an effort to grasp a confused global state. These poems dig through grief, loss, ageing, technological frustrations, environmental degradation and nationalism; unfolding across a variety of scales, from global spheres to the most intimate of domestic spaces. Exploring everything from climate change and scientific discovery, from the death of parents to resource extraction, divorce and career changes, these poems touch down on whale extinctions and lounges in international airports, on debris slides and suiciding pilots, on sinkholes, astronauts, grocery-store magazines, earthquakes, and even sinking ferries and pop stars.

When did you begin the poems that have found their way into your latest collection, Outside, America?

Outside, America began in 2013 on a sidewalk in Los Angeles. I remember the day very clearly. I was making my way to the geography conference I attend every year. I was walking past the Walt Disney Concert Hall (a Frank Gahry building) and mulling over a news report I’d just read. A small plane had crashed through the roof of a suburban family home, propellers barely missing a sleeping infant. It seemed so impossible. A plane crashing through the roof of a house with no warning. I was imagining how fragile humans are while at the same time thinking about the unparalleled damage we do to each other, to non-humans, and to the planet.

I often think about poems and poetry as I walk. That afternoon, under a very bright blue California sky, I was contemplating finishing off a long book-length single poem (Skeena, Caitlin Press, 2015) and wondering about what might come next, about why I didn’t write short poems and what that said about my poetic practice. Suddenly, against a backdrop of the sleek curvy metallic walls of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, on a California afternoon with news of somewhat surreal events whirling through my brain, I realized I wanted to write a collection of short poems that fused senses of strange almost surreal happenstance with eminently tangible happenings like global warming, divorce, and death of parents.

So Outside, America began.

Your poems are rooted in Canadian and American places. With the topic of walls and borders dominating the media in recent months, how does a sense of place or belonging inform your poetry?

Sense of place and poetics are inextricable from each other in my writing practice.

I have for long periods of time visited, lived, and worked in the United States, always however with the deep sense of being Canadian and wanting to return to Canada. Which is not to be mistaken with a nationalistic nostalgia about Canada: Canada is a deeply problematic country built on still not addressed colonial violence and cultural genocide.

Still, my sense of belonging, or not, is central to my sense of place – so feelings of being out of place, or experiences of dislocation, of living in marginalized places, or being angry that people are violently forced from place, all circle into my writings about place. I believe humans’ writing of and imagining of space actually forms place: consequently, through poetic renderings of place, of geographies, I try to imagine (and hence make) different ways of being in and sharing space. It may sound hopelessly naïve, but I believe poetry can change the places that make up this world.

How does your interest in science influence the poems?

My PhD is in the disciple of Geography. I work in a faculty of medicine. I am surrounded every day by discourses of science. I have a great respect for science and the answers it provides. I also think science can be beautiful – the languages of science, the findings of science, the potential of science…these are all creative and esthetic, despite many scientists not saying so directly. I have, for almost as long as I can remember, been fascinated with science as a source of understanding the world. But I think the sciences and scientists need the arts, need creativity. I do not think, however, that artists can simply demand scientists take up our creative tools without reflecting on our own gaps in knowledge-making.

I think in our creativity and in our creative expressions, artists have a responsibility to dialogue with scientific ways of understanding the world, to become more fluent in scientific expressions. I do not believe that science (or science alone) will solve the complex challenges facing the human and non-human world. Nor do I believe that artists and creative works are the sole answer. I believe the sciences and the arts must work together, speak to each other. I hope my poems are literal representation of that belief.

With the environment being an ongoing topic of megawatt concern on the planet—films and exhibits like Anthropocene bring the issue into art and new conversations—what effects do you hope your poetry will have?

To behave differently, which is the only thing that will change the future of humans and many other species on this planet, human have to both think and feel differently about our circumstances and actions. As a colleague and mentor has said to me for more than 20 years, it takes both the head and the heart.

I believe in the power of science and policy and logic and government to encourage different kinds of thinking. I believe, however, that art has the power to change the way humans feel – how we feel about things like extinctions and poverty and war and desertification and global warming. Ideally poetry – and my own poetry – will play some small part in people feeling differently. Ideally, my poetry will reach hearts (and hopefully minds too) and encourage (especially in humans of great privilege) some changes in behaviours.

At its core, humanity is prevalent in your new collection. How difficult do you find reflecting the social anxieties or conflicts that pervade life in your poetry?

Mostly I write about big issues (like social anxieties) by focusing on micro-scale domestic and diminutive articulations of them. I think that’s one of poetry’s great gifts to the world: at the scale of letters and words and lines, poetry (or a single poem) physically and materially reflects how large (sometimes impossibly large and complex) issues can be rendered and distilled to small, but deeply impactful and powerful, digestible contemplations. There is a great force in the intimate. I think radical change can occur through and within the smallest of acts.

Are you excited about sharing these poems to live audiences? What are your hopes?

Reading poetry is always a pleasure. Which is not to say that I don’t get nervous and jittery EVERY TIME I present my poetry to a live audience. But I think poetry should translate off the page with the same force as it presents on the page – while eyes and breath should scan with the on-the-page-poem, and while a written poem should show and display itself textually in innovative and thoughtful fashions on the page, I also believe in the orality of a poem, in poetry more generally. I believe in the power of a poem partly resting in its ability to be read, ingested through being heard. I hope the poems in Outside, America expand beyond the page when I offer then to a live audience.

And, although it’s not often possible in more traditional poetry readings, I also really appreciate the opportunity to chat with folks about my poetry, or about their questions about writing and poetry more generally. I find engaging with a live audience, around poetry, to be inspiring – I often learn a great deal from people who care enough to be present at a poetry reading. Their presence always feels like an honour.

Who are some poets you have been admiring lately?

I could not be more excited about an Indigenous resurgence in poetry in Canada. Billy-Ray Belcourt. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. Jorden Abel. Liz Howard. Philip Kevin Paul. Joshua Whitehead. Gwen Benaway. These are poets with words and work to unsettle colonial nations and norms. Writing poetry to transform worlds into something better. Of course, I also deeply admire poets like Marilyn Dumont, Lee Maracle, Jeannette Armstrong, and Rita Bouvier: I believe there is a rich rich history of Indigenous poetics in this country – and, because I’m interested in the outside and in America, that history and contemporary poetic expression can now be read in dialogue with poets like Layli Long Soldier, whose book Whereas was nothing short of miraculous.

I think non-Indigenous Canadians would do well to read, deeply, and listen and learn. While it’s not their jobs to do so, and while of course, their voices are for themselves and each other, these Indigenous authors are providing non-Indigenous guidance. They are putting on the public record demands for truth, accountability, and transformation.

Working as you do with the League of Canadian poets, you must experience a major connection to poetry across the country. Does this influence your own writing? Do you think the average poetry reader in Canada (if that can be measured/identified) has a clear understanding of just how much poetry is created each year in our country?

I suspect Canadians who read poetry are well aware of how much poetry is created in Canada every year. The thing is, I don’t think many Canadians actually read much poetry! It’s a pretty small world, the world of Canadian poetry. I sometimes worry we’re a little too myopic, existing in a kind of echo-chamber. I think poetry feels, for many people who haven’t embraced it or who don’t already write it, like something they “don’t get”. Something they toiled through and with during school. Something that made them feel dumb, or like they were missing some huge important “ah-ha” moment in their reading. While I love the complex acrobatics and leaps of language that poetic space opens up, I also appreciate the ways that very simple and accessible language can bring fresh even unsettling feelings to the familiar.

Outside, America is not a dense theoretically complex text. I take a certain amount of pride in bringing my poetry to diverse audiences – I read poetry to geographers, I try never to turn down invitations to read to high school students or city councillors. I share poetry with medical students and doctors. I love the fact that The League of Canadian Poets has launched national Very Small Verse contests and has supported poetry being written for the public on Valentines’ Day in Union Station in Toronto.

I believe in letting people know it’s ok to not “get” anything from a poem other than their own relationship to it. I think in this time of deeply polarized politics, in times when I worry people are searching for being the MOST right by proving other people and perspective wrong, reading poetry provides lessons about how to sit quietly with the unknown, how to not worry about being right or wrong, how to think (even a tiny little bit) differently about the earth and our human place in it.

Sarah de Leeuw is an award-winning Canadian writer and researcher whose books include Unmarked: Landscapes Along Highway 16 (NeWest Press, 2004), Front Lines: Portraits of Caregivers in Northern British Columbia (Creekstone Press, 2011), Geographies of a Lover (NeWest Press, 2012), Skeena (Caitlin Press, 2015), and Where it Hurts (NeWest Press, 2017), which was a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award for nonfiction and a finalist for the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional BC Book Prize. She lives in Prince George, BC. In 2013, Geographies of a Lover won the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize, the annual BC Book Book Prize for the best book of poetry by a British Columbian author. In 2017, de Leeuw was one of 70 scholars appointed to the Royal Society of Canada and inducted in the Society’s Celebration of Excellence.