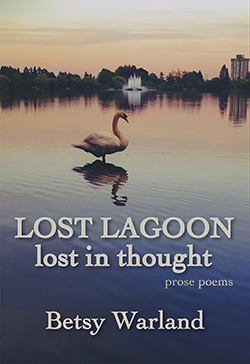

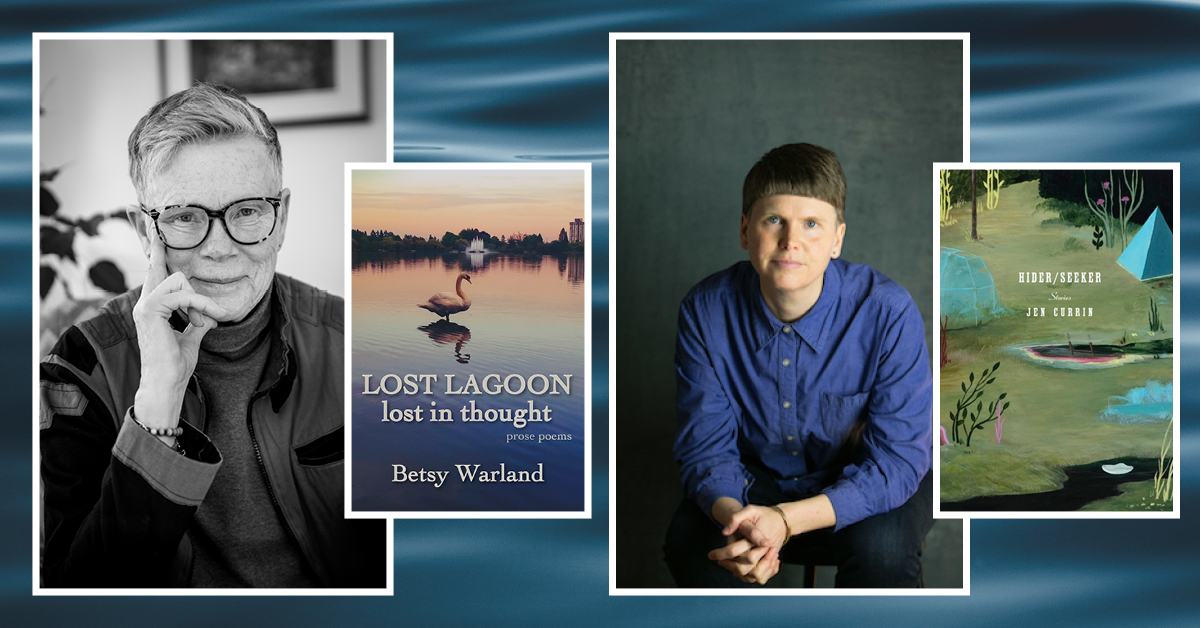

Jen Currin: In your book Oscar of Between: A Memoir of Identity and Ideas (Caitlin Press, 2016), you use a fictional name—Oscar—to work in creative nonfiction. You turn to this device again in your most recent book, Lost Lagoon/lost in thought (Caitlin Press, 2020), with the character of The Human. What compelled you to use this device in both of these nonfiction books?

Betsy Warland: Having never fit into a category, choosing a second given name (Oscar) was incredibly liberating. Pivotal. It enabled me to find an identifying term that finally fit: “person of between.” This enabled me to investigate my core, societal concern about our rampant, massive societal deception that is literally destroying us. In turn, the name “The Human” surfaced of its own accord in the first piece I wrote. It surprised me. Yet was the most honest signifier for our relationship to nature. So these two names (Oscar and The Human) aren’t fictional devices. They accurately signal my narrative position. Acknowledge the particular keyhole for me (the writer), and subsequently the reader, to look through, engage, and interpret the idiosyncrasies of the narrative. In terms of creative nonfiction, the majority of my books have been book-length narratives that use devices and strategies of fiction, poetry and nonfiction. Genre constraints are perfect for some narratives and at odds with others.

JC: You dedicate Lost Lagoon, in part, to Canada’s most famous early Indigenous poet, Pauline Johnson, and you weave pieces of Indigenous history throughout the text. Could you talk about this decision? At what point in the composition of the book did this aspect come in?

BW: My quest when writing is to entrust myself to narrative’s clues and cues. They teach me how to interpret and follow the narrative’s specific guidance. This involves each narrative’s particular make up: emotionally, intellectually, socio-politically, as well as artistically and often spiritually. The act of perception is incremental. It’s erratic and unpredictable. Over the years, my Buddhist practice has made me keenly aware of this. Given this is a narrative’s inherent makeup, I adhere to the order in which the narrative reveals and gradually gathers itself. This enables the reader to experience the discovery quest. I call this erratic process: approach, retreat, return. This cycle remixes those three positions unpredictably until incrementally, we grasp what the narrative is telling us. In Lost Lagoon, there are fifty-five prose poems. In the 1st prose poem, The Human remarks “…let’s begin with its name: Lost Lagoon. Its very name is a conundrum. How can one misplace a lagoon?” By the 8th prose poem, The Human has done some research and discovers that Pauline Johnson named it Lost Lagoon. Subsequently, The Human comes across other related details about Johnson’s life, writing, and performances. Toward the end of writing the first draft, The Human decides to read Johnsons’ Legends of Vancouver and is deeply affected by it. As residents here, we barely know the thin layer of recent history, and The Human “wonders—how would we…be changed if every one of us read these legends?”

JC: Throughout Lost Lagoon, there is a careful attention to the natural world, the animals and plants of Lost Lagoon, as well as close observation of the human beings who frequent the lagoon. How much of writing would you say is attention and observation? In what ways is writing a form of seeing?

BW: For me, this kind of seeing is evident in your writing, Jen. Writing is a form of seeing (but also can be a form of obscuring). Being with the lagoon was a form of close attention. Observation is removed, fleeting and it confirms our biases. Attentiveness relies on setting aside what we already “know,” and abandoning our habits of impatience and assumptions. I was amazed again and again at how much lagoon life would reveal itself once it trusted my being quietly with it, learning from it, delighting in it, lingering with it. When I realize that I am in a specific narrative territory it throbs with an irresistible vitality. I never really know what the next word, phrase, or line will be, nor, sometimes, what it is essentially about. When I think “Ah-ha. I’ve got this!” it fizzles out. Seeing anew, or for the first time, is what it is all about. This is when the narrative offers us its particular gamble and grace.

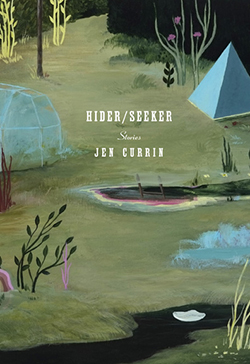

I will also start with a narrative position question as this interests me in your book too. In several stories in Hider/Seeker (Anvil Press, 2018), the narrator seeks to extricate themself from the various gendered expectations/limitations with the narrative. To me, this signaled “the map is not the territory.” Did this defamiliarization open up more options for how to tell these stories?

JC: This is such a cool and complex question—I feel like I’ll need to ruminate on it for some time to really have a worthy answer, but for now I can say that being queer and nonbinary definitely gives me a different perspective on the heteropatriarchy, and that there are many queer stories that are not being told, and I hope to tell some of them. In terms of how to tell them—choices of form, point of view, etc—I am sure that some of the stylistic choices I make are influenced by my queer nonbinary identity, but it’s hard for me to articulate or even really know how much this part of my identity plays a part in these choices….

BW: This is your first book of prose. How was your perceptual process of creating and writing these stories different from your previous books of poetry? I’m particularly curious about the modality of collage so prevalent in your books of poetry. Was it set aside or operative, but altered?

JC: My processes for poetry and prose are very different in many ways. For poetry, I’m a notebook writer, and as you note, primarily a collagist. I take my notebook with me everywhere I go, and am always observing, reading, listening, and writing things down. Then, when I sit down to make a poem, I draw from the range of sources in my notebook as well as what’s around me at the time of composing. Fiction works differently. I often have a glimpse of a character I want to bring to life, or a situation I have questions about. The idea will simmer away and I’ll take notes for it and put it in a folder with the tentative name of the story. This will go on for months or even years. Then when I feel I have enough material and get that strong inner urge that it’s time to tell a particular story, I start writing a draft. And the drafting process is very laborious and there will be many, many versions of the story before it’s done. In some ways the processes are similar in that, in both cases, I’m collecting material for some time before I actually sit down to write a draft. And for fiction, even when I have a solid finished draft, I still “collage” in additional elements—little details or images in a scene, a piece of dialogue, or even an entire scene that occurs to me later and needs to be woven in. Also, my process of character creation involves a sort of collaging, as I usually work with composite characters, pulling different characteristics/habits/etc. from real life people and from my imagination. So there’s an element of collage there as well, although my stories do not (yet?) involve the sometimes strange juxtapositions and leaps of my poems. They aren’t collage pieces like, for example, Burroughs’s cut-up fiction.

BW: Most of your characters seek insight and a healthier life but are hiding from themselves (and others). In the game hide-and-seek, the winner is the last one to be found by the seeker so we absorb this strategy early in our lives! Struggles with addiction appear quite frequently in these stories along with the necessary cover-up stories. I relished how characters like Somchai and the old woman kept upending the various expected narratives. How would you describe the interaction between your own Buddhist practice and your writing (particularly in this book)?

JC: You are not the only local writer who thinks I’m a Buddhist! Years ago I was talking to a student and she told me another student had recommended a class of mine and told her “Jen’s a Buddhist who rides transit.” Which is such a funny statement for so many reasons. I’m not sure why he thought I was a Buddhist—maybe because I do mindfulness in class? More recently Jónína Kirton referred to me as one of her Buddhist writer friends. I am honored because the Buddhists I know are pretty cool, but I am not and doubt I ever will be a Buddhist. I’m quite interested in some Buddhist ideas though, and have read quite a few Buddhist texts. I’ve also stayed at a couple of monasteries and sometimes sit with a Zen group on Monday nights. I guess now that I write all this it makes sense that people mistake me for a Buddhist! But to get to your question: in Hider/Seeker, I was interested in the idea of people hiding spiritually/emotionally and also seeking deeper truths in their lives. Several of the characters go on spiritual retreats—one of them goes to a center that is initially a Buddhist monastery but later gives up this affiliation as the head monk becomes disenchanted with the religion. In terms of my own spiritual practices and their connection to writing… I guess one connection I see is that the practice of mindfulness/meditation can be similar to the concentration that’s needed to produce good writing. I talk about writing fiction as “going into the cave”—I have to cut out all distractions, put in earplugs sometimes (or even rain noises from a video on YouTube—a condo is being built across the street!), pull down the blinds (even light can be too much stimulus), and go deep into the story, ignoring everything else. I’ll have this feeling inside—almost like I’m saying to the story, “I want to get really close to you. Please let me.” In meditation, I only reach this level of concentration very rarely—but the practice is in trying, even if my mind always wanders. Writing can be a refuge—the notebook is a sort of refuge, a place a person can enter, like a church, a temple.

One reply on “Two Queer Writers in Conversation: Betsy Warland and Jen Currin on Their Recent BC-published Books”

A lovely conversation. Thank you.