The widely acclaimed authors talk about their recent projects, breaking the rules of form, and sense of place.

Wayde Compton: Both of your books Dear Current Occupant and Junie are, in different ways, thematically concerned with place and home. What motivated you to address these themes in your work and how do those two texts treat them differently?

Chelene Knight: Home, place, and belonging are themes that I naturally gravitate towards. These themes arise for me because of the complex relationship I have with my own history, especially as it relates to understanding my father’s history and where he and his family come from. As I slowly, finally begin to build a relationship with him (after 40 years of not knowing anything) I’ve come to learn so much about how a place can play an integral role in how we show up in the world, the decisions we make, and how to write intentionally about both. I’ve often wondered if it’s possible to have a connection to a place one has never been and if that connection could be as strong as the one we have to the places we’ve known our whole lives.

In Dear Current Occupant, I explore the places I’ve known my whole life. The places where I’ve come to learn what it means to cling so desperately to a sense of home, but never really have it, grasp it, or dream about it. In the book, I walk readers to and through all the homes I grew up in as a young girl. We stop, touch the walls, and look out the windows. In doing I also look for pieces of myself left behind.

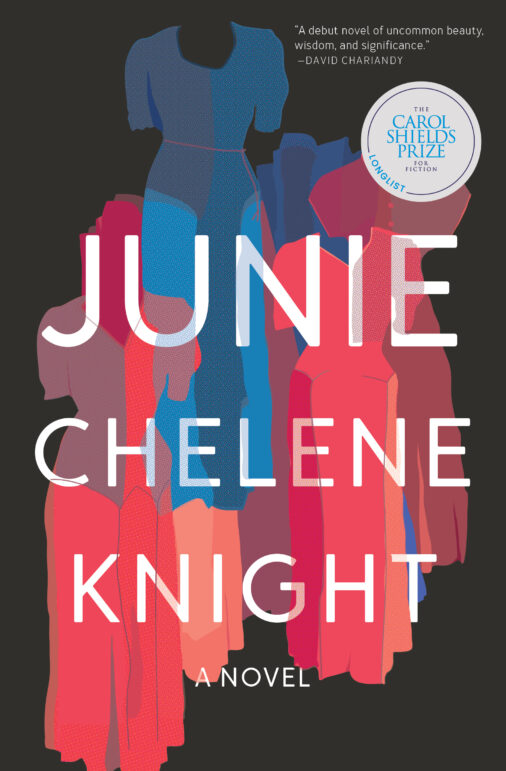

In Junie, a fictional story, we watch Junie try to do the same reflective work, but she’s searching for home within herself with her Strathcona neighborhood—Hogan’s Alley—as an ally. In this book my character Junie learns about herself (and how to love her seemingly flawed mother) through her connection to the new place where she has set down roots. The place then takes over, latches on, and guides her. Love has always been there for her and she had in fact sensed this her whole life.

Both books look at place from different angles and ask very different questions.

To me your writing also connects to place. When I read your work (whether poetry, fiction, or nonfiction) I can’t help but think about how you build worlds that feel magnetized, readers are pulled into these worlds and are compelled to begin their own investigation of these places. It was from you that I learned about Hogan’s Alley and my desire to investigate started to swell. How do you write about place in this way?

When you produce writing about a place you know well, or a place you have a direct relationship to, it becomes an active subject in your work. I think readers sense that.

Wayde: One thing I encourage my students to do is trust in the local. Too often emerging writers seem to think they ought to write about other places, perhaps because those places seem more archetypal or famous. But a writer’s relationship to the local is important in many ways. You both influence and are influenced by your locality. You know its textures and its nuances. So when you produce writing about a place you know well, or a place you have a direct relationship to, it becomes an active subject in your work. I think readers sense that. Also perhaps the most significant exploration a person can do is in their own backyard. Because as much as you know, there are always surprises, gaps that reveal how relationships and social landscapes really work. The funny thing is I’ve suggested to students that they set a specific work in Vancouver, or wherever they are from, and will sometimes get pushback because, as they say, they’ve never seen such a story placed there. And that, I say, is exactly why you should do it.

On a different topic, I realize we both appear to be writers who use different forms. Like me, your books are poetry, non-fiction, and fiction. What’s your reason for working in different forms? What are the challenges? Do you think you will keep doing that?

Chelene: One thing I have been thinking about for the last five years is how genre informs genre. I used to believe that a writer should pick a lane and stay in it—or maybe this is simply what publishing as an industry wants us to do—but I’ve come to learn that each project demands a specific container, shape, and blueprint, and sometimes that then means deviating from the path you were on. I started my writing career in poetry and quickly learned that poetry can be a foundation for all genres: master the art of a poem and you are golden.

But I also discovered that even though I was learning to write in new genres, poetry wasn’t going to go quiet into the night, nor did I want it to. I watched poetry show up in everything I wrote and read. I read poetic fiction by Jamaica Kincaid, Toni Morrison, and Ian Williams. In their books I felt the vibration and rhythm needed to convey a specific message and tell a story. When I realized that I could use the “rules” and templates of various forms to suit the unique needs of the specific project, a new world of possibilities opened up for me. Poetry gives me full license to play with language in ways that maybe nonfiction doesn’t. Fiction allows me to tell a story bigger than just my own. When I took my first stab at fiction, I intentionally used poetry to bend the “show don’t tell” rule of fiction in order for my story to be told in my voice at the time. I love having all of these genres at my disposal. As a writer, this is a powerful toolkit to hold.

Wayde: I agree! For me, at least, the project precedes the form. Whether what first comes to you is a premise, a character, an image, or a phrase, you move from there in search of the right container, as you say, for it.

Chelene: In speaking about genre I can’t help but think about how we come to find our place in the writing world. How important is a writing community to you and what are the ways in which a writing community can change as we grow as writers?

In creating a fictionalized version of Hogan’s Alley I could encourage readers to dream: to dream of a place that they used to know that maybe is no more.

Wayde: My writer friends and mentors were very important to me when I was in my twenties and starting. Absolutely crucial. Now, in my fifties, it’s different. Some conversations from those days, when things were foundational, have remained conversations in my own mind over the years. I still think through stuff George Bowering said to me about writing 30 years ago. And I still will sometimes pick up a conversation from a friend from those days, even strands of thought that might have lain dormant for years and then suddenly become relevant to a current project. Some remain in my mind as rhetorical conversants. Or I just think, “What would she think of this project? How would he read this?” So maybe what happens to one’s writing community as the years go by is that it becomes more integrated into your own process. It’s less about literal community interaction. At least, that’s how it’s gone for me. On the other hand, I think of my current students and colleagues at Douglas College as part of my present writing community. I think it’s important to understand students as real and serious writers sometimes before they are able to do that themselves, and part of that is listening to what they say and think about writing. So that’s a type of active writing community I’m involved in.

Let’s talk about Junie and Hogan’s Alley and Vancouver history and Blackness. My writing career has been different from many of my peers because my subject has often been Black historical, and therefore I found myself nudged into the position of activist and pundit. There’s an urgent need for Black history and recognition in this city especially, and so a creative writer who engages with this topic can find themselves asked to wear other hats. Sometimes I’m okay with this and other times I regret that I haven’t had a writing life where I get to just be a writer. I’ve never quite reconciled it. So my question is, has the spokeswoman role been thrust on you yet? Any thoughts on that generally?

Chelene: That’s such a fascinating question. I do feel like I’ve been nudged into certain activist roles but I’ve had to push back on that because I don’t want to be in a role that doesn’t make sense for me as an individual. There will always be an invisible pressure to serve in certain ways, but we have to think about what our own specific contribution should be. We can’t all be on the front lines so to speak.

I am not a historian, but I decided to set my novel in 1933. I am not a Hogan’s Alley expert, but wanted to set my novel in that neighborhood. I found that with Junie, I was asked so many questions about why I decided to fictionalize the neighborhood versus bring it back to life. The answer for me is simple even though the decision took some time to think out. In creating a fictionalized version of Hogan’s Alley I could encourage readers to dream: to dream of a place that they used to know that maybe is no more. If I highlighted the living that took place then I would need to make sure that folks weren’t simply fixated on the historical facts. That was difficult in that I knew I’d be pushing out a very specific (historical) audience and that was a chance I was willing to take.

My life as a writer is so important to me so I can understand that desire to just write. But I’ve decided to focus on my language because that’s really what I have control over. Instead of wanting only to write, I want to infuse creativity into everything I do, and that shift in language has really helped me speak about what I do at my literary studio: “I’m a writer and I help other writers write in a healthy way for life.” That’s it!

Wayde Compton has written five books and has edited two literary anthologies. His collection of short stories, The Outer Harbour, won the City of Vancouver Book Award in 2015 and he won a National Magazine Award for Fiction in 2011. His work has been a finalist for two other City of Vancouver Book Awards as well as the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. Compton has been writer-in-residence at Simon Fraser University, Green College at the University of British Columbia, and the Vancouver Public Library. He is currently working on a re-imagining of The Argonautika by Apollonius of Rhodes as a surrealist slave narrative set on the west coast of North America in the 18th century. Compton teaches in the faculty of Creative Writing at Douglas College in New Westminster and Coquitlam, BC.

Chelene Knight is the author of Braided Skin, Dear Current Occupant, and Junie. She is currently working on a commissioned book on Black self-love and joy. Let it Go is forthcoming with HarperCollins Canada in 2024. Chelene is also the founder of Breathing Space Creative Literary Studio.