What makes us remember? Why do we forget? And what, exactly, is a memory?

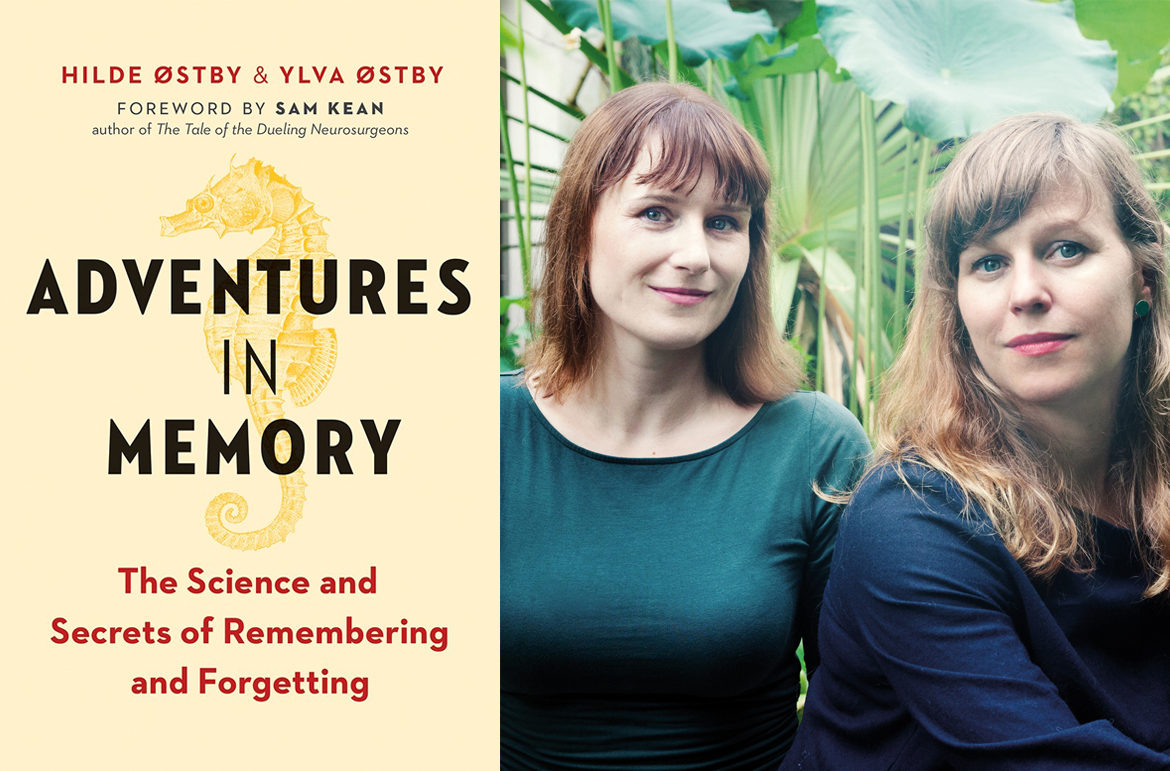

With playfulness and intelligence, two Norwegian sisters—novelist Hilde Østby and neuroscientist Ylva Østby—answer these questions and more. Adventures in Memory: The Science and Secrets of Remembering and Forgetting (Greystone Books) offers an illuminating look at one of our most fascinating faculties.

You cover such broad ground in Adventures in Memory, pairing findings from neuroscience research with insights from literature, psychology, history, anthropology, architecture, mythology, and more. Why did you choose to incorporate so many different perspectives?

Memory is so much more than the physiological processes within and between neurons in the brain. It concerns all of us, and makes an impact on—and is impacted by—all aspects of culture and society. We wanted to show through vivid examples why memory matters. We were also fascinated by the collective memory of human civilization—the history books and literature that allow us to learn from our shared past. We felt that had to be reflected in the book as well.

In Adventures in Memory, you interview some fascinating characters, including people with extraordinary memories as well as those with extraordinary problems remembering. What were some of the highlights from these conversations for you?

Our conversation with Adrian Pracon, one of the survivors of the terrorist attack and mass shooting in Utøya, Norway, made a lasting impression on us. It is difficult to remain unmoved by his account of how the traumatic memories have tormented him. He took us on a trip to the Island where he and so many teenagers and young people were shot down. That experience, walking through the beautiful spring scenery while he showed us where he hid and where he saw people being killed… it was such a strong contrast. How can you live with memories like that and integrate them into your life, without being crushed by them?

We also talked to several people who had lost memories of their childhood and youth, in part or completely, and we were fascinated by how they coped with what we would consider terrible circumstances. It is really possible to live a happy life without all of your memories? In a way, their story is true for all of us – we forget far more than we remember. We just never think of all the stuff we have forgotten!

What is a “cumulative” memory? Is this different from what you call a “false” memory?

…all memories, true or false, are constructed in our minds.

A false memory is by definition something that has never happened, which you remember as if it were real. Cumulative memory, on the other hand, is a term we use to describe memories of events that have been repeated many times, like taking the bus to work or cuddling your child at bedtime. Because we don’t remember each separate instance the event took place, we construct a compilation of all those instances, so to speak. These compilations are similar to false memories in that they are not necessarily true renderings of the past, just approximations. All those times you took the bus were unique, and likely none of those experiences were exactly like what you imagine when you think about “taking the bus.” But really all memories, true or false, are constructed in our minds. There isn’t as much of a difference between “true” memories and false memories as we like to think.

Many of the people you interview in Adventures in Memory have gone to outrageous lengths to improve their memory. We meet taxi drivers who had to train for years to navigate London’s crooked streets; quiz masters who diligently read their morning newspaper with a notepad and pen at their side; and a World Memory Champion who uses decks of cards to memorize lists of completely useless things. What drives us to these extremes? Why is remembering so important to us?

Remembering gives us a sense of being in control and on top of things, whether it is control of performance and achievement, of our personal history, or of time itself. But for most of us, this is an illusion. Even if some of our experiences are etched into our brains as memory traces, they always come back to us transformed—perhaps even better than before, as Marcel Proust, author of In Search of Lost Time, might argue. It’s funny: we fear the loss of control that comes with forgetting, but most of us don’t even know what it is that we can no longer remember.

…we fear the loss of control that comes with forgetting, but most of us don’t even know what it is that we can no longer remember.

There’s a very provocative line in the book: “Forgetfulness is underrated.” Can you expand on this idea?

Remembering and forgetting are both integral parts of memory. Forgetting is our brains’ way of tidying up so that the memories that remain can stand out and shine. Forgetfulness is nature’s way of showing us that time that has passed is best reconstructed, often with flaws, rather than remembered in perfect detail. And think about it: isn’t it a relief to forget sometimes? Good riddance to all those mundane seconds of our lives and all those bad feelings! And when it comes to the good experiences, forgetting what it was like to ride that roller coaster the first time around makes the experience all the more exhilarating on your next visit—if roller coasters are a good thing, that is.

What was it like to write this book together as sisters?

It was both a lot of fun and a challenge. We contributed equal amounts to the book, through writing, experimenting, and generating ideas. Going places and interviewing people together was really great, as was setting up experiments. As sisters, we are more honest with each other than most people, which actually helps with the writing process. Let’s just say that this adventure has given us a whole bunch of new memories together.

Ylva, you’re a trained neuroscientist. Did you learn anything new while working on Adventures in Memory?

Definitely! There are so many winding roads of memory research that I wouldn’t normally go down in my day-to-day work. And as a clinician, I mostly see clients with memory complaints, so learning more about people with superior memory abilities was an eye-opener. Also, learning from Hilde that memory was considered a divine art by alchemists in the 16th and 17th centuries was really fascinating. Writing this book has truly been inspiring for my research.

Hilde, you have some thought-provoking ideas about the connection between memory and writing, drawn from your own experience as a journalist and novelist. Can you tell us more about it?

While writing this book, it dawned on me how closely related the art of storytelling and the act of remembering are—how our stories, and all of the most beautiful pieces of literature, are structured just like memory itself. So learning more about memory definitely taught me more about writing.

Also, as a historian, I realized how much focusing on our individual, fallible memories can be a mistake, especially in a court of law. False memory research started in the 1970s because researcher Elizabeth Loftus wanted to examine why we so often wrongly accuse people of crimes they never committed—and do so with so much certainty. In truth, our memories are very unreliable, and she proved that through a number of spectacular experiments, including tricking people to think that they loved asparagus or hated eggs.

I believe memories are supposed to be collective; together we can remember more than we can alone. Our stories, together, connect us to each other, keeping us within a shared reality.

Lately, there’s been a lot of emphasis on mindfulness, on learning to live in the present moment rather than letting the mind wander. But in the book, you write that “mindfulness has given future thinking a bad name.” Can you explain what you mean?

Mindfulness is actually not about living in the present; that is a common misunderstanding. Instead, it involves a controlled form of mind wandering, in which one anchors the experience in the present moment. So it’s actually more correct to say that the misunderstandings around mindfulness and the hype it has created has given future thinking a bad name. People mistake mind wandering with rumination and loss of control. But rumination is not the same as mind wandering; it’s really a form of stagnated thinking. In life, we need these free moments of mind wandering to let our mental time machine run, process our memories, and develop a vision for our future.

Hilde Østby is a writer and editor and the author of Encyclopedia of Love and Longing, a novel about unrequited love that was published to critical acclaim in Norway. She has a master’s degree in History of Ideas from the University of Oslo.

Ylva Østby is a clinical neuropsychologist with a PhD from the University of Oslo who devotes her research to the study of memory. She is also vice-president of the Norwegian Neuropsychological Society. She lives in Oslo, Norway.

Filled with cutting-edge research and nimble storytelling, Adventures in Memory: The Science and Secrets of Remembering and Forgetting (Greystone Books)is a charming—and memorable—adventure through human memory. The book is available October 9, 2018.

One reply on “Adventures in Memory with sisters Hilde Østby & Ylva Østby”

[…] Østby and neuroscientist Ylva Østby—answer these questions and more. Adventures in Memory: The Science and Secrets of Remembering and Forgetting offers an illuminating look at one of our most fascinating […]